Global transportation is shifting irreversibly, as China propels global EV adoption faster than anyone predicted, and it's fundamentally reshaping the world's automotive landscape.

Total electric car sales hit over 17 million in 2024, a 25% increase from 2023 - and the latest stats from Q1 this year showed a jaw-dropping 35% increase in sales compared to Q1 the year before.

EVs now make up more than 20% of new car sales worldwide, according to the International Energy Agency's (IEA) Global EV Outlook 2025 report.

And China remains a gravitational epicentre for this rapid transformation, manufacturing 12.4 million electric vehicles last year - an eye-whopping 70% of the world’s total EV output.

More than 80% of that production originates from its domestic OEMs such as BYD and SAIC.

Despite growing international ambitions and foreign investment interest, less than 2% of that output occurred outside Chinese borders, indicating deliberate design rather than a lack of interest.

The EV race isn't just about what people want to buy or new inventions. It's critically tied to how policies are set, who controls key resources, and strategic regional power.

The IEA suggests that China’s EV dominance stems not only from its scale or competitive pricing but also from its upstream advantage - specifically its control over battery-grade material processing, from sources such as lithium, cobalt and graphite.

Want to know more? Mission Critical: Yes, China's driving our energy future

This control enables Chinese producers to ensure supply chain security at a time when other nations are grappling with fragmented and vulnerable value chains.

Speaking on the Middle Kingdom's state-owned media outlet CCTV earlier this year, BYD CEO Wang Chuanfu claimed that Chinese EVs were 3-5 years ahead of the rest of the world.

That may be a conservative estimate, considering Ford CEO Jim Farley confessed to driving a Chinese-made EV himself and that the country was a decade ahead in tech and efficiency.

The time difference, whatever it may be, will steer global demand toward the cheaper and more advanced Chinese brands.

So far behind

By contrast, carmakers in the West are met with fundamentally different and more difficult sets of challenges.

Take for example Europe's automotive sector - once home to the world’s second-largest EV market.

The IEA says the EU car market showed signs of stagnation in 2024, with the continent’s sales remaining flat compared with 2023 despite an increase in the range of available models.

That slowdown is down to a double-squeeze of subsidy withdrawal and stagnating CO2 regulations.

Government incentives have been scaled back across key markets such as Germany and the UK with no new regulatory pressures to stimulate consumer demand.

The situation in the United States is more of a mixed bag.

While sales rose by 10% in 2024, federal reversals in EV tax credit eligibility and state-level pushback against clean vehicle mandates have fostered a climate of strategic ambiguity.

Automakers currently lack the clear policy direction needed for long-cycle investment, says the IEA, cutting its 2030 U.S. EV share forecast in half - from over 40% in 2024 - to just 20% this year.

All about the batteries

Under the hood, battery chemistry fundamentally reshapes the state of play.

Lithium iron phosphate (LFP) chemistries - previously considered suitable only for low-range options - make up ~40% of global EV batteries due to their low-cost and high safety record.

Chinese heavyweights the likes of CATL and BYD have heavily invested in LFP for mass-market production.

Yet the West’s automakers largely still use nickel-manganese-cobalt (NMC) formulations, which, despite offering higher energy density, come with higher costs and geopolitical risks.

The IEA report shows that China still controls two-thirds of global cobalt refining and 60% of lithium processing.

That means that even when mining activities take place elsewhere - such as in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) or Australia - midstream control of these critical materials goes to the Middle Kingdom anyway.

As EV demand continues to accelerate, the critical minerals bottleneck could rapidly become the most consequential strategic choking point of the next few decades, especially if a U.S.-China trade war ensues.

Find out more: Mission Critical: China's plan to choke lithium tech supply

While supply chains are under strain, automakers are establishing strategic approaches to vertical integration.

BYD already has one of the most aggressive strategies: manufacturing its own batteries, controlling its own cathode supply, and even scaling its own shipping fleet to reduce dependence on third-party logistics.

That comprehensive approach - heavily and long-supported by government subsidies - has resulted in reduced costs per vehicle, enhanced margin control, and surging global exports.

Elon Musk saw this coming, and so Tesla did the same, with investments in battery cell manufacturing in Nevada, lithium supply deals in Texas and sourcing concentrate from as far away as Australia’s Pilgangoora mine.

Overreliance

However, even Tesla is still reliant on external battery partners, particularly China's CATL, while most legacy automakers remain dependent on Chinese suppliers right across the value chain.

And while companies like Volkswagen, Stellantis, and Hyundai-Kia are constructing gigafactories - their timelines are protracted.

The IEA observes that for most OEMs in the West, in-house battery manufacturing “will not achieve meaningful scale until after 2027”, granting pricing control over to Eastern manufacturers.

Pricing wars are already redefining competitive dynamics.

BYD’s decision to cut prices - twice already this year - for 22 models, has triggered a wave of discounting across China's highly competitive EV market and abroad.

For instance BYD's Seagull compact EV now starts at just US$7,780 a pop.

This ‘race to the bottom’ is seen as a deliberate strategy to eliminate price as an entry barrier and to force market consolidation.

Legacy automakers - burdened by their higher fixed costs and fewer in-house capabilities - have no way to respond to these price reductions in the short to mid-term.

They've already been accepting investment and buyouts from Chinese not-so-newcomers since way back in 2010, when still little-known in the West Geely Automotive bought an 80% stake in Volvo back in 2010.

The carmaker also owns the brands Lotus, Polestar and Zeekr.

Find out more: Volvo: Thousands of jobs go as owner Geely cuts costs

The implications for global trade are enormous.

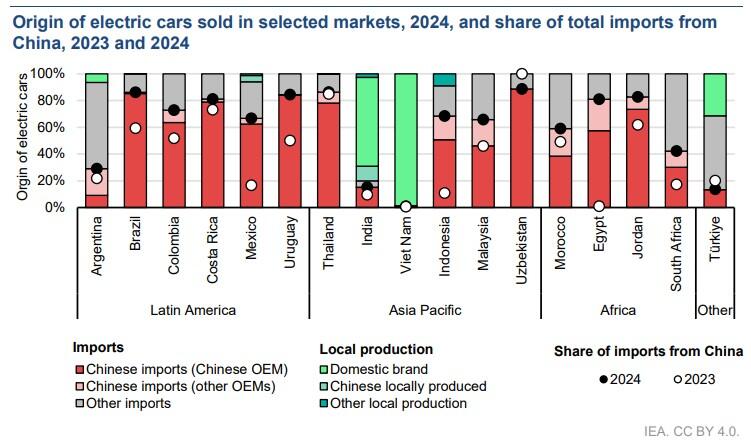

Chinese EV exports to Southeast Asia, Latin America, and Europe are growing exponentially.

In Europe alone, Chinese brands now make up more than 11% of the EV market from just 3% in 2020.

While the EU has initiated anti-dumping investigations, tariffs alone may not be sufficient to offset the advantages of scale economics and the upstream stranglehold of Chinese manufacturers, the IEA says.

China already has a foothold in the global car sector thanks to its EV value chain initiative.

By the time, or even if the rest of the world catches up, the West will find it an extremely steep hill to climb back into carmaking competitiveness.