It sure is mission critical for the West so far in 2025 and we’re just nine days into the new year.

Welcome to Azzet's Mission Critical. Our weekly column that lays out the ebbs and flows around critical minerals supply chains from production and refinement to manufacturing and consumer products.

Since the 80s, through cheap labour and questionable environmental mining practices that the West conveniently turned a blind eye to, China has provided manufacturers across the globe with low-cost alternatives to supply chains of raw and refined critical minerals.

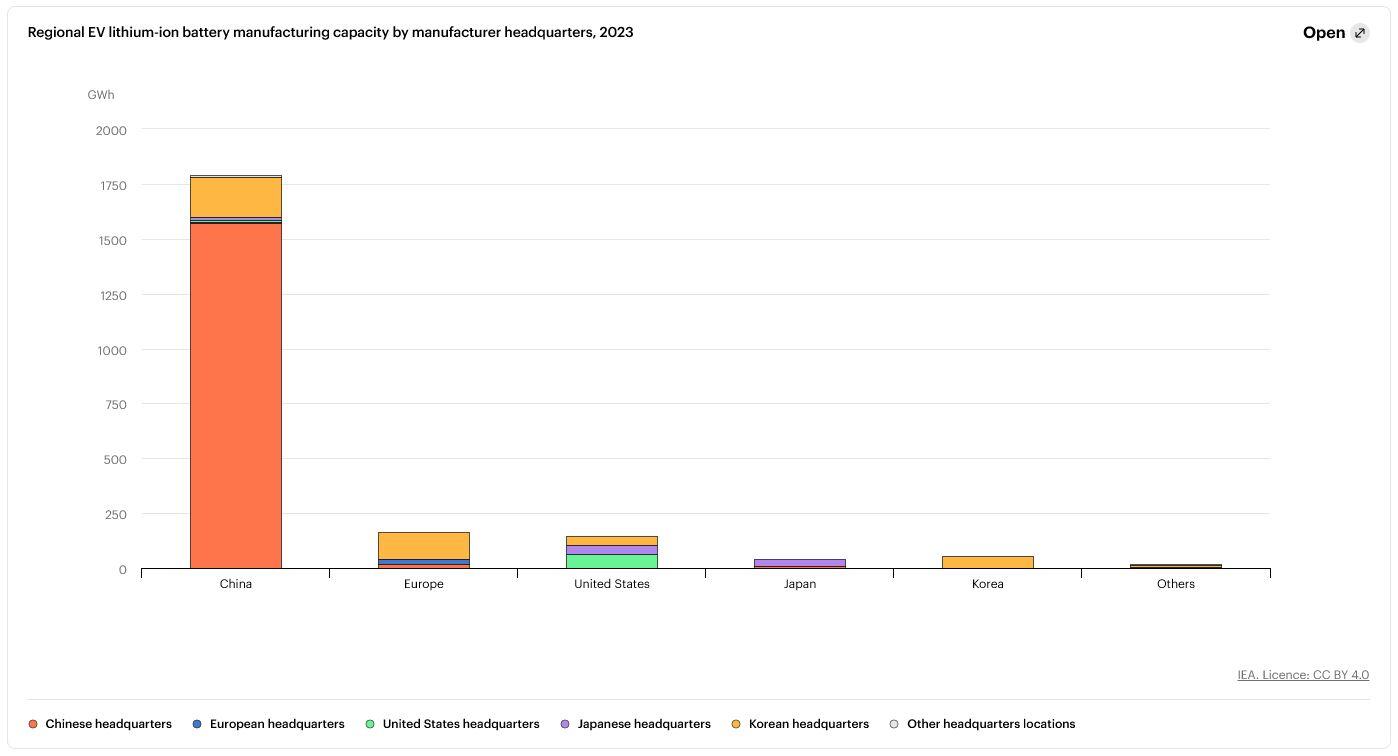

Fast-forward to today, and the Middle Kingdom now has a monopoly over a vast swathe of production and refining of most of them - to the tune of a whopping 70-90% of the global market share, says thinktank The Carnegie Institute.

That 70-90% is across every stage of the value chain for current-generation lithium-ion battery technologies, from mineral extraction and processing to battery manufacturing.

The US-China economic coercion battle

Lately, the country has sought to weaponise its hegemony over these strategic metals and wield it as a political tool against U.S. geopolitical plays by restricting exports of critical minerals graphite, gallium, germanium and antimony (so far) last year - elements used in batteries and semiconductors.

The Chinese government then doubled down on that move, sending another economic salvo aimed at the U.S. and its allies. It announced restrictions on “dual-use” tech used for both civilian and military use in response to a U.S. crackdown on the semiconductor industry.

And just last week, Asia’s superpower proposed that on top of those curveballs, it’ll now target a ban on Chinese companies exporting technology used to extract, refine and manufacture lithium products to foreign entities.

The Chinese Communist Party (CCP) announced its proposed restrictions on the export of battery and lithium processing-related technologies, including highly sought-after direct lithium extraction (DLE) and lithium iron phosphate batteries (LFP) innovations.

The move is seen as retaliation against President-elect Donald Trump’s plans to increase tariffs to 25% on imported materials from China, Mexico and Canada – including raw and processed materials.

So what? Isn't the West diversifying its supply chains?

Well, yes it is. However, these things take a lot of time, capital and assurance from miners and refiners that investors will see a return on investment (ROI) by the time projects get into production. Pouring billions of taxpayer money into subsidising high-magnitude projects. (one only has to look at the history and current development of America's giant Mountain Pass rare earths mine in the Mojave desert to get a picture).

Here's a picture anyway:

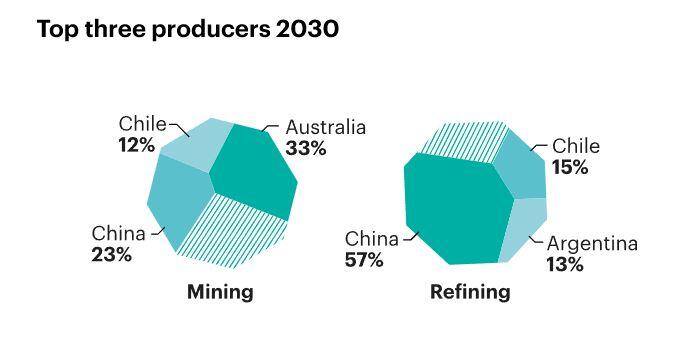

China currently - and is forecast to - still dominate lithium refinement with 57% global market share by 2030, according to the International Energy Agency (IEA).

Meanwhile, EV sales are set to rise from 13.9 million sold in 2023 to over 30 million in 2027. This is according to a recent BloombergNEF report.

And that demand for batteries is not just for EVs themselves, it’s for energy storage too.

Why? Because by 2040, it’s predicted that over two-thirds of vehicles on the roads across the globe will be EVs that need to be charged - a number that will weigh heavily on our grid networks and reliability.

With those kinds of numbers, it’s no wonder the IEA has projected lithium demand to skyrocket up to 42 times its consumption in 2020.

China’s fiercely competitive strategies have put pressure on battery technology improvements and refinement in the West. This is done by flooding supply chains with low-cost alternatives - thereby pricing countries out of developing their own domestic markets.

Especially for the now manufacturer-preferred LFP batteries, which can be developed to include super-fast-charging capabilities, cold temperature performance and higher energy densities.

LFP batteries have been traditionally inferior to the once-preferred ternary lithium batteries due to their superior output.

Yet technological advancements - mainly stemming from China - are improving LFP batteries and being snapped up by manufacturers at competitive prices.

Lithium tech squeeze

2023 saw LFP adoption rates rise staggeringly in China, the world’s largest EV customer, reaching over 70% of market share. Carmakers elsewhere, such as Tesla, Volkswagen, GM and Ford are increasingly using them as ternary alternatives.

A year later, state-backed industry leader CATL showcased its new LFP battery tech at the 2024 Beijing Auto Show, unveiling the Shenxing PLUS that powers EVs to drive up to a whopping 1000km.

If enacted, China's recent proposal will give the CCP control over where its homegrown technological advancements are rolled out.

The same is true for DLE extraction techniques for lithium from brine ponds - an alternative to traditional mining practices used to mine battery metal from hard rock sources such as WA's Pilbara region.

Lithium from brine uses techniques similar to those used in the oil and gas sector with an evaporation separation method that incurs high costs to develop. It's used in South America's Lithium Triangle between Chile, Argentina and Bolivia one of the world's largest sources of lithium hydroxide from brine ponds in salars (salt lakes).

A long road ahead

To counteract this, international battery giants such as Samsung, LG and SK On are also developing LFP production lines with multi-billion-dollar investments in North America, South America and Europe.

It could take years, even decades, for countries to establish ex-China downstream, mid-stream and upstream supply chains online.

In the meantime, it seems that as long as President Xi Xinping and the CCP are in control of them, the West will have to bow to China’s economic coercion.