Sustainability in 2026 is set to be defined by a balancing act between near-term economic and political pressures and longer-term environmental and social risks. According to S&P Global's Top 10 Sustainability Trends to Watch in 2026, businesses, governments and investors are adjusting strategies to reflect a more fragmented policy landscape, intensifying climate impacts and the rapid expansion of energy- and resource-intensive technologies such as artificial intelligence.

A central theme is the shift towards a more pragmatic framing of sustainability. Corporations are increasingly linking environmental and social initiatives to risk management, operational resilience and profitability, rather than relying solely on climate or ESG narratives.

This evolution comes as political cycles, regulatory divergence and economic uncertainty complicate long-term planning, especially for global firms operating across multiple jurisdictions.

Geopolitics and fragmentation

Global coordination on sustainability is weakening as multilateral approaches give way to more regional and national strategies. Divergent energy and climate policies among major economies, particularly the United States and China, are shaping trade flows, technology supply chains and investment patterns.

Emerging and developing economies, often the most exposed to physical climate risks, face added challenges in accessing finance for adaptation and resilience.

Energy policy illustrates these contrasts. Fossil fuels remain a significant component of global primary energy demand, while renewable energy technologies such as solar and wind continue to expand rapidly.

However, reliance on clean energy supply chains and critical minerals frequently implies dependence on China, raising strategic and trade-related risks.

Climate adaptation and resilience

As the likelihood of exceeding the Paris Agreement’s 1.5°C warming goal becomes more widely acknowledged, adaptation and resilience are moving to the forefront.

More frequent and severe extreme weather events are increasing economic losses, damaging infrastructure and disrupting supply chains. Investment in protective infrastructure, resilient systems and risk reduction is therefore gaining urgency.

Adaptation spending is emerging as a major investment theme. Financial institutions and insurers are incorporating physical climate risk more directly into credit analysis and pricing.

Yet corporate disclosure and planning on adaptation remain uneven, with many sectors still lagging despite rising exposure to climate hazards.

Energy transition under strain

Energy expansion and decarbonisation are advancing in parallel. Rapid growth in electricity demand - driven in part by AI and data centre expansion - is straining grids and complicating emissions reduction goals.

While renewables capacity continues to grow, the pace of expansion is uneven, and grid modernisation is a critical bottleneck.

Electrification of transport, growth in battery storage and development of low-carbon fuels such as sustainable aviation fuel are continuing, but progress varies by region and policy support.

Trade measures such as carbon border mechanisms are adding complexity to global energy and industrial supply chains.

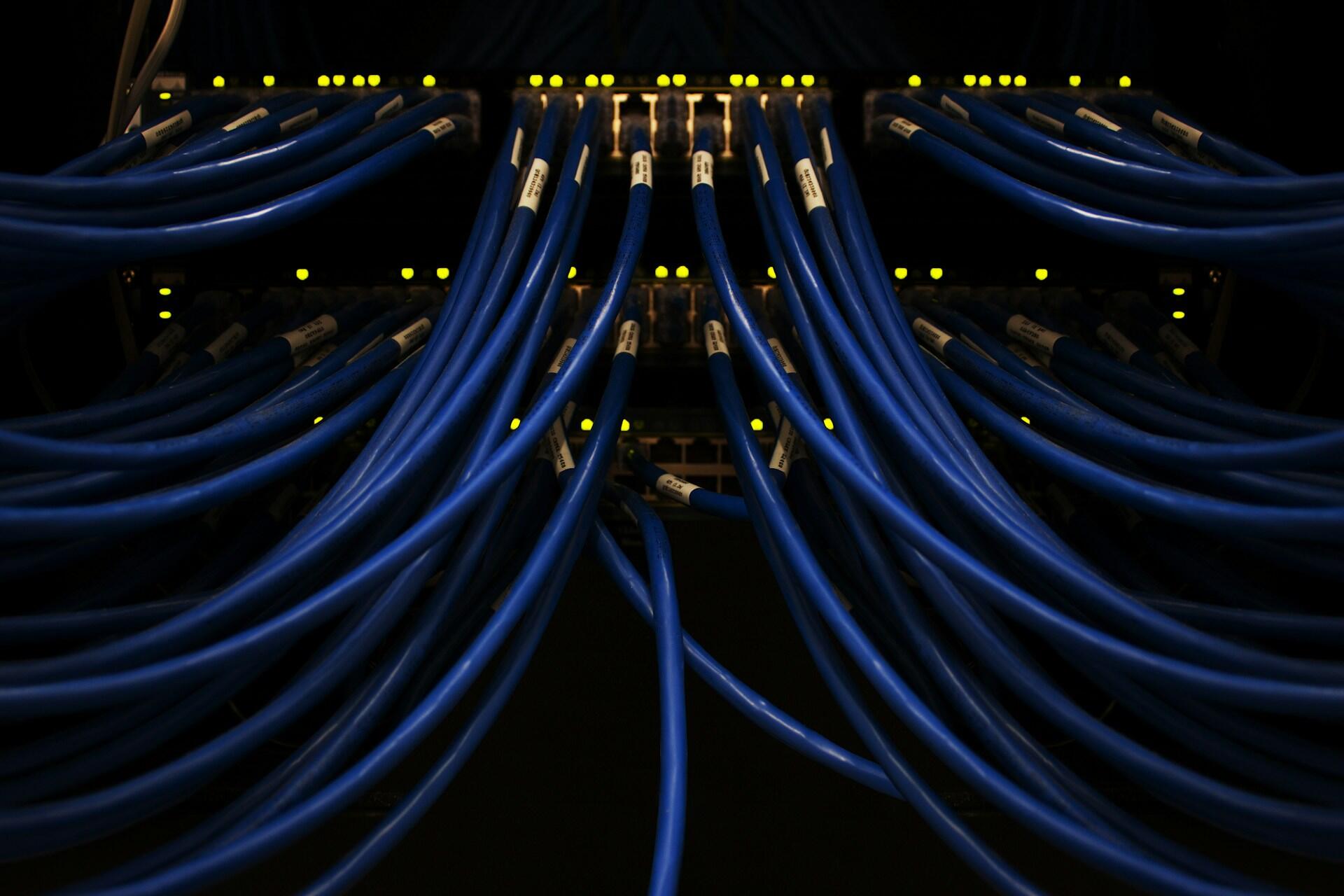

AI and data centre pressures

The expansion of AI-driven data centres is creating new sustainability challenges. Rising electricity and water demand from large computing facilities is increasing pressure on local infrastructure and natural resources.

In some regions, this growth is contributing to higher power prices and renewed reliance on fossil fuel generation, where renewable deployment cannot keep pace.

Although many technology companies maintain net-zero and water stewardship commitments, the aggregate impact of sectoral growth is drawing greater public and political scrutiny.

Resource constraints, particularly water stress in already vulnerable regions, are likely to feature more prominently in policy debates.

Water and food systems

Water risk is becoming more visible across sustainability discussions. Climate change is intensifying droughts, floods and water stress, with implications for agriculture, food security and industrial operations.

Many data centres and manufacturing hubs are located in water-stressed areas, heightening competition for resources.

Financial impacts from water-related risks are expected to grow in the absence of adaptation measures.

As a result, water-focused financing instruments and integrated resource management strategies are gaining traction among investors.

Meanwhile, in a separate report, the United Nations recently declared the onset of an era of “global water bankruptcy”, warning that nearly three-quarters of the world’s population lives in countries deemed “water insecure” or “critically water insecure”, with 4 billion people experiencing severe water scarcity at least once a month.

Supply chains and nature

Trade tensions, protectionism and shifting regulatory priorities are altering the sustainability focus in supply chains. While some jurisdictions continue to advance due diligence and emissions-related trade measures, overall policy momentum is uneven.

At the same time, climate hazards and resource constraints continue to threaten globally dispersed supply networks.

Nature and biodiversity loss are also becoming more financially material. Degradation of ecosystems can undermine access to key resources and reduce the resilience of economic activity.

Emerging disclosure standards and regulations linked to deforestation and nature-related risks are increasing pressure on companies to assess and report their impacts and dependencies.

Standards, regulation and finance

The reporting landscape is becoming more complex. Some regions are scaling back or revising sustainability disclosure rules, while others are moving to adopt or align with global standards.

This divergence is creating legal and operational uncertainty, but also reinforcing the role of voluntary and internationally recognised frameworks.

Financing needs for sustainable development, particularly for adaptation and resilience, are rising at a time of competition for capital from defence, security and technology investment.

Blended finance, transition finance and carbon pricing mechanisms are among the tools expected to play a larger role in mobilising funds.

Demographics and the workforce

Population aging is emerging as an additional structural factor. Shrinking working-age populations in many economies may constrain growth and increase pressure on social systems.

While automation and AI offer productivity gains, these may not fully offset labour shortages, adding another dimension to long-term sustainability planning.

Overall, 2026 is shaping up as a year in which sustainability strategies become more tightly integrated with core economic, security and operational priorities, reflecting a world where environmental and social risks are increasingly viewed through the lens of resilience and competitiveness.