Will the Australian Labor Government's new $1.2 billion critical minerals strategic stockpile initiative finally push us properly downstream as an important global supplier of refined metals? Or will the red tape and high capex of creating a sustainable refining industry again keep us out of the higher-profit links in the value chain?

A government taskforce is being established to finalise the scope and design of Australia's Critical Minerals Strategic Reserve - two new mechanisms that will build upon critical minerals investment to stockpile reserves of high demand and scarce minerals.

- National Offtake Agreements - through voluntary contractual arrangements the Government will acquire agreed volumes of critical minerals from commercial projects, or establish an option to purchase at a given price, holding security over these assets as part of the Strategic Reserve.

- Selective Stockpiling - the Government will establish Australian stockpiles of certain key critical minerals produced under offtake agreements as required.

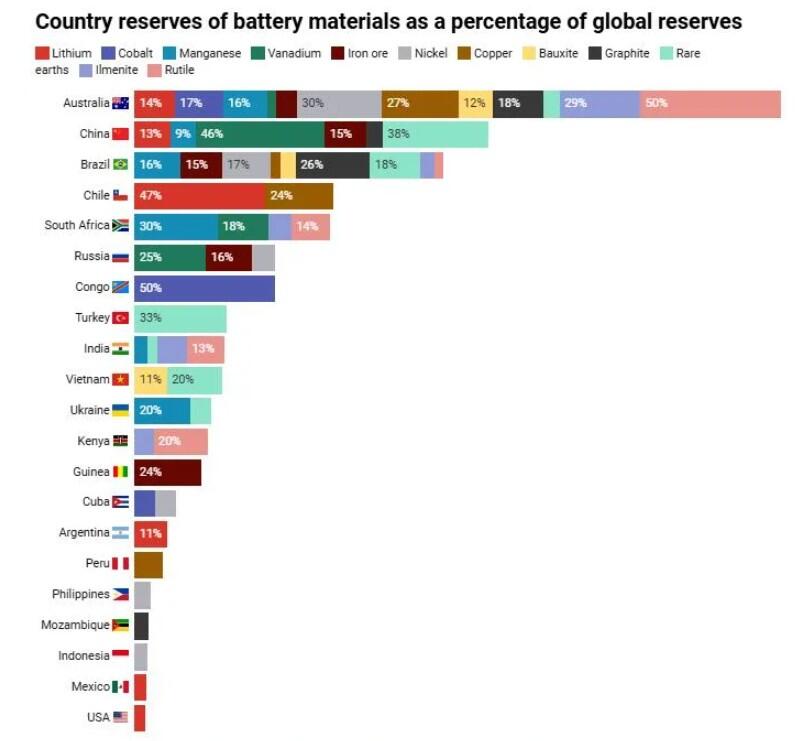

It makes sense, since Australia has the largest reserves of battery materials in the world.

The creation of the Strategic Reserve and the expansion of the Critical Minerals Facility is supported by the Labor government's $7 billion Critical Minerals Production Tax Incentive.

It signals a serious move beyond simply mining and exporting raw materials, toward making Australia a reliable supplier of refined, high-value minerals.

The strategy is akin to what the US is attempting with its Defense Production Act and the EU is doing with its Critical Raw Materials Act.

The Australian Strategic Policy Institute (ASPI) says Australia’s proposed critical minerals strategic stockpile framework can play an important role in the global supply chain.

“But it will do so only if paired with serious policy around downstream industry, long-term offtake and international partnership,” ASPI says.

Australia: Feedstock for China

For decades, Australia has cornered itself as a raw materials exporter, with governments unwilling to invest in providing incentives for further processing and refining capabilities - thus missing out on value-adds further down the minerals supply chain.

Sure, there are examples of downstream refining capabilities being implemented within our shores, such as the Kwinana lithium hydroxide plant south of Perth.

Yet that’s owned in a joint venture between ASX-listed IGO and China’s Tianqi Lithium and fed by the JV’s 51%-owned (49% US-based Albemarle) Greenbushes mine - one of the largest hard rock lithium deposits in the world.

And, even though it’s roughly three quarters-owned by companies with ties to the West, all that lithium hydroxide (LiOH) - a high-grade refined material used in battery production - paradoxically goes to Chinese offtake partners.

As lithium prices fell in 2023 and coupled with high labour and running costs, Tianqi canned a Phase II expansion of the 24,000 tonne per annum (tpa) Kwinana facility, which would have doubled LiOH output.

The case is eerily similar to Australia’s iron ore industry - also known as China’s breadbasket for steelmaking where roughly 68% Fe is shipped in bulk at around $100/t to the Middle Kingdom and comes back as part of a manufactured product such as a car.

Let’s say there’s roughly one tonne of steel on average in each vehicle that costs about $35,000 - now price that into a 1.5 tonne new car, and… well, you get the jist - Australia is missing out on the profit margins further downstream the value chain.

A nuanced approach needed

As the US-China trade war threatens to significantly shift current supply chains for the materials required to push towards clean energy goals, Australia’s mineral wealth could become a vital cog in the emerging global economic paradigm shift.

While backing the re-elected Albanese government's new policy initiative, ASPI hopes it’s ready to tackle its complexity.

“The reserve is a smart, pragmatic policy targeting both supply and demand aspects of Australia’s critical minerals sector,” ASPI says.

“Executed properly, it will shore up Australia’s economic and geopolitical interests in the face of global energy transition, geopolitical fragmentation and economic coercion.

“Although it’s an important step, if policymakers and industry leaders are serious about delivering sovereign capability, they must build durable partnerships and plan for market instability.”

ASPI says building a resilient and competitive alternative to China’s critical minerals dominance is a global strategic challenge and a task far more challenging than Australia alone can solve.

“It demands deep, sustained co-operation with like-minded partners, particularly Japan, the United States, South Korea, India and the European Union,” the think tank said.

ASPI says the government plan will allow the nation to move beyond simple export models into building integrated supply chains, with strong partnerships and scaling up capabilities.

“The critical minerals sector offers Australia a once-in-a-generation opportunity to move beyond the traditional resource economy and lead in enabling the global energy transition and building high-value technology ecosystems,” ASPI says.

“This layered approach to supply, demand and value-add is exactly what Australia needs.”