The International Monetary Fund reckons global growth will slow from 3.3% in 2024 to 3.2% in 2025 and 3.1% in 2026. What's driving that deceleration matters as much as the numbers, especially when you consider the risks that could make it worse - and several are now materialising.

The IMF's mid-October World Economic Outlook report stated "the rules of the global economy are in flux", with uncertainty about stability remaining acute despite tariff deals that have tempered some extremes since the U.S. introduced higher levies back in February.

The report's outlook has advanced economies forecast to grow just 1.5% in 2025-26, with the U.S. cooling to 2%, while emerging markets are tipped to grow just above 4%.

World trade volume growth is expected to hit 2.9% in 2025-26 - well off 2024's 3.5% clip.

What drove the flux in October

Just days after the IMF's mid-October World Economic Outlook warned about China's rare earth export controls, Trump and Xi struck a deal that suspends those controls for a year.

That's one threat temporarily off the table, but AI stocks are repricing, labour force shocks are accelerating, and fiscal vulnerabilities are worsening exactly as the IMF warned.

Primarily, it was President Trump's sweeping tariffs - starting with 25% on Canada and Mexico and 10% on China in February, then the April 2 "Liberation Day" announcement that hit virtually all trading partners.

The Peterson Institute for International Economics found the tariffs took average U.S. rates to their highest levels since the 1930s Great Depression, though subsequent deals and exemptions have brought them down from April highs.

But it's the constant changes - rates shifting daily, deals struck then threatened again - that's cranking up the volatility.

Advanced economies are forecast to grow just 1.5% in 2025-26, with the U.S. cooling to 2.0%, while emerging markets will moderate to just above 4% growth.

World trade volume growth is expected to hit 2.9% in 2025-26 - well off 2024's 3.5% clip.

The Fund's chief economist, Pierre-Olivier Gourinchas, told the October briefing that the tariff shock is "further dimming already-weak growth prospects", pointing to weakening labour markets and persistently above-target inflation as hallmarks of a negative supply shock.

Early 2025 resilience was driven by companies rushing to import goods ahead of tariffs - so-called front-loading - but that effect is unwinding, and new freight orders have plummeted.

China's debt-deflation spiral

As a sidenote, a consistent concern for commodity markets and global trade is China, where the Fund says the economy "teeters on the edge of a debt-deflation trap" more than four years after its property bubble burst.

If China doesn't grow, neither do resources-heavy exporters such as Australia. While analysts have already baked in China's downturn, the situation has deteriorated even further since the assessment.

S&P Global Ratings now forecasts China's primary property sales will fall 8% in 2025 - downgraded from a 3% drop predicted in May - and another 6-7% in 2026, pushing the downturn into its sixth consecutive year.

More than 90% of China's 70 tracked cities reported month-on-month price drops since late 2023, with all 70 cities posting declines in September 2024, May 2024, and December 2023.

The residential price index has fallen by over 14% since August 2021.

International investors are fleeing. BlackRock and Carlyle have offloaded commercial buildings at steep losses, while HSBC and Standard Chartered warn of higher defaults on Chinese real estate loans.

In April, Fitch Ratings downgraded China from A+ to A, citing "sustained fiscal stimulus needs amid deflationary pressures" and structural erosion in the revenue base.

Financial stability risks are "elevated and rising" as real estate investment contracts and credit demand remain weak.

Beijing's response suggests it's written off a property recovery.

Chinese policymakers are prioritising tech development over real estate support, according to analysts tracking the Central Committee's four-day meeting that wrapped up in late October.

While manufacturing exports have buoyed growth, the Fund reckons Beijing's pivot toward sectors like EVs and solar panels through subsidies "may have contributed to significant overall misallocation of resources and lackluster aggregate productivity gains" - a red flag for commodity demand.

Four downside risks - three now materialising

And so IMF research landed on four threats to the baseline forecast - all tilted to the downside.

Three of the four key risks are now materialising:

- AI stocks are repricing as markets question spending payoffs

- labour force shocks are cutting projected GDP growth by half a percentage point,

- and fiscal vulnerabilities are worsening with U.S. debt at 100% of GDP and interest costs exceeding $1 trillion

- The fourth, China's rare earths export bans have been - at this stage at least - lifted.

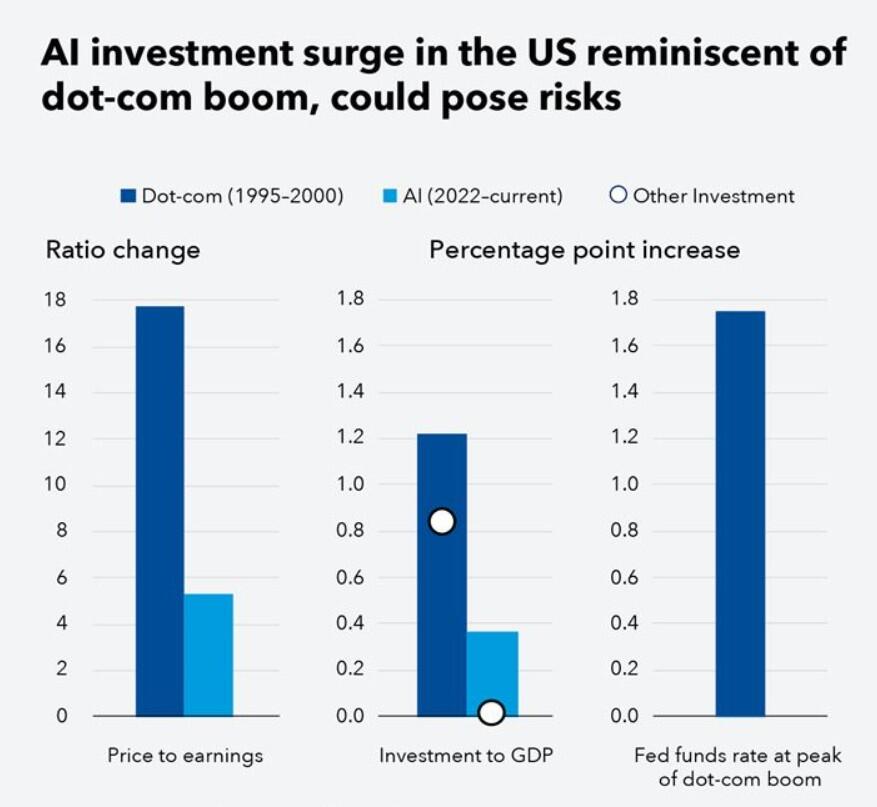

First up was the risk of an abrupt repricing of tech stocks triggered by disappointing AI earnings and productivity gains, which might mark an end to the investment boom.

Given the "exuberance of financial markets" surrounding AI, the ripple effects for macrofinancial stability would be significant. That repricing may just be unfolding now.

Meta suffered its worst day in three years on 30 October - the same day Trump and Xi met - dropping 11% after lifting 2025 capex guidance to US$70-72 billion.

The market is showing scepticism about AI spending payoffs despite strong earnings, with Alphabet and Microsoft again lifting capex expectations the same week.

Last week, Palantir fell 6% despite exceeding expectations, dragging other AI stocks down and pushing the VIX above 19.

Axios noted the central risk: “It's a highly expensive bet and nobody knows if it will pay off. Companies might overbuild capacity."

If the largest tech companies with fortress balance sheets overbuild, they can pause capex. But if companies start taking on debt to finance development and demand doesn't catch up, that could create systemic risk.

Second, labour supply shocks from restrictive U.S. immigration policies threaten to crimp expansion in economies facing ageing populations and skill shortages.

Gourinchas noted a "very sharp reduction in the share of foreign-born workers in the labour force in the U.S." - another body blow on top of tariffs.

More than 1.2 million immigrants disappeared from the U.S. labour force from January through July, according to Census Bureau data analysed by Pew Research.

It's projected that Trump's immigration crackdown will reduce the workforce by 6.8 million by 2028 and 15.7 million by 2035.

America's average annual GDP growth is expected to drop about half a percentage point through 2035 as a result.

Sector impacts so far have been acute. California's workforce dropped 3.1% from May to June after immigration raids, with the steepest declines among non-citizens.

Construction employment fell 0.1% in the 10 states with the highest concentration of undocumented workers, while other states saw 1.9% growth.

Meanwhile, agriculture lost 155,000 workers from March to July.

And there's no evidence that U.S.-born workers are filling vacant jobs as Trump officials predicted.

Third, the IMF says fiscal vulnerabilities and financial market fragilities may interact with rising borrowing costs and increased rollover risks for sovereigns.

It warns that "prolonged policy uncertainty could dampen consumption and investment" - a reference to the constantly shifting tariff rates.

The IMF's October Fiscal Monitor - released alongside the growth outlook - warns global public debt will exceed 100% of GDP by 2029, with “the greatest concern being financial turmoil, driven by fiscal financial feedback loops”.

The U.S. hit that milestone this year. Federal debt reached 100% of GDP in fiscal 2025, with the Congressional Budget Office projecting it will climb to 118% by 2035 - surpassing the 1946 post-WWII high of 106% by 2027.

That's the fifth consecutive year of deficits above $1 trillion, pushing FY2025's shortfall to $1.8 trillion.

Interest payments on the debt surpassed $1 trillion for the first time, making net interest the second-largest federal expenditure behind social security - exceeding both defence and Medicare.

The environment has changed dramatically from the post-GFC period. Between the financial crisis and the pandemic, rising debt was accompanied by falling interest rates, keeping interest bills stable.

Now rates are up considerably, and the path forward is highly uncertain, says the Fund.

The U.S. Treasury Department reckons immediate fiscal reform requires primary surplus increases of 4.3% of GDP. Delaying to 2035 would require 5.1%, while delaying to 2045 would require 6.3%.

And so the IMF assessment points to a lower-growth equilibrium shaped by debt, demographics, and deglobalisation - and that equilibrium is arriving faster than expected.