While talk of Russia’s deteriorating economy is not new, what’s becoming increasingly evident is that the war-driven boost, courtesy of heavy budget spending on its military, is now well behind the ailing former soviet economy. While the Russian President Vladimir Putin acts like he doesn’t care, it’s becoming glaringly evident that the country’s economic resources needed to sustain its war effort at current levels are fading fast.

Surplus funds that have been used to boost the Russian economy are drying up.

So much so that economists now suggest Russia’s appetite for a peace deal with Ukraine has more to do with some brutal economic realities than any philosophical resolve to end the bloodshed.

According to Russia’s Finance Ministry, the budget deficit reached 4.88 trillion roubles (US$61.1 billion) between January and July this year, equating to 2.2% of GDP.

During the same timeframe, government spending surged by 20.8% to 25.19 trillion roubles (US$317.8 billion).

While the Russian economy has been teetering on the brink of recession for months, financial authorities are now fully aware that taking actions to slow growth in a bid to avoid runaway inflation is a delicate dance.

Nothing to see here

Despite Russia’s central bank Governor Elvira Nabiullina’s insistence that the economy isn’t cooling excessively under high interest rates, the economy is struggling to meet even the most cautious central bank estimate for growth this year.

According to data from the Economy Ministry, gross domestic product (GDP) expanded by just 1.1% over the first seven months of the year, barely above the lower bound of the central bank’s 1%-2% growth forecast for 2025.

However, despite the effects of tight monetary policy, policymakers refuse to take business concerns over high borrowing costs seriously.

Having argued that the economy was merely exiting a period of overheating as expected, the central bank kept the benchmark interest rate at a record level of 21% through the end of June.

Growth slowed in July, with GDP rising 0.4% compared to the previous year, down from 1% in June.

Industrial production growth also decelerated to 0.7% from 1.9% as the manufacturing sector cooled, while seasonally adjusted industrial output fell for the second consecutive month.

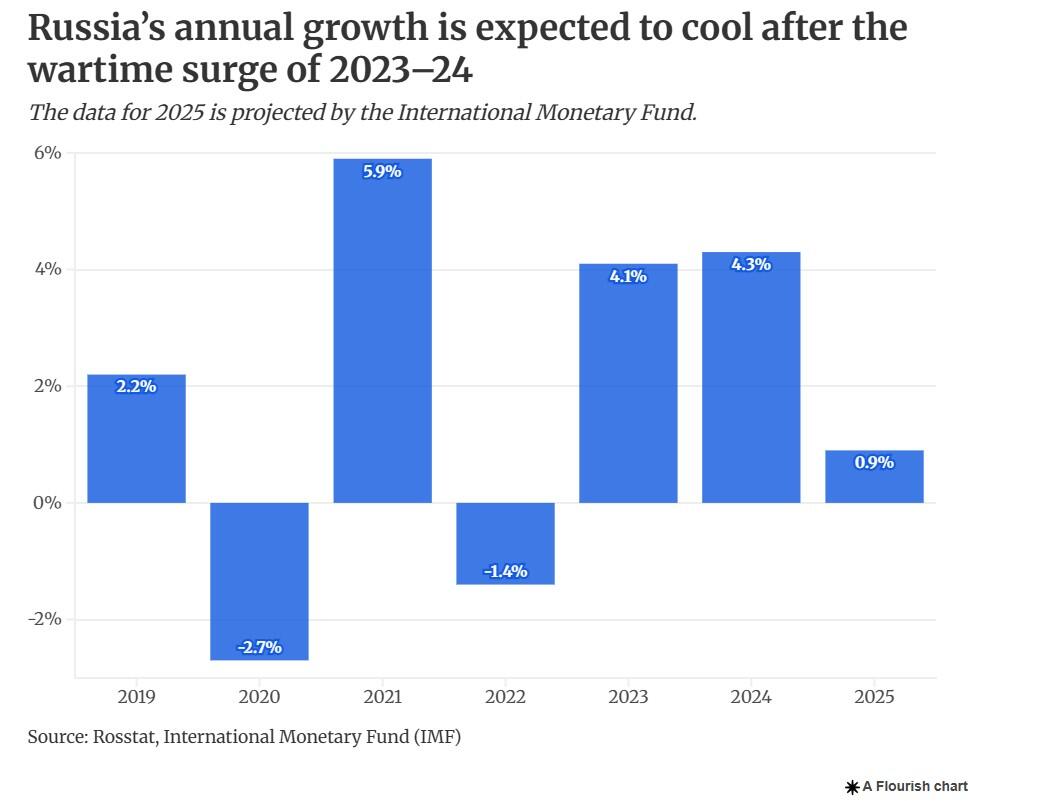

Meanwhile, Dmitry Polevoy, investment director at Moscow-based Astra Asset Management, foresees full-year GDP growth of around 0.7% if the situation doesn’t improve; this compares with 4.3% growth in 2024.

Polevoy estimates the growth in Q2 to be near zero after seasonal adjustments.

Unsurprisingly, in July, the International Monetary Fund lowered its growth forecast for the country from 1.5% to 0.9% for 2025.

Business investment tumbles

While the central bank governor expects investment activity to remain robust this year, despite the high cost of borrowing, independent business surveys suggest nothing could be further from the truth.

According to Elena Astafyeva, commercial director at the TenderPro procurement platform in Moscow, high interest rates and falling corporate profits are taking a significant toll on investment activity.

TenderPro’s survey results reveal a 13% drop in the number of business investment projects this year.

"Given the inertia in business activity indicators and a high base effect, economic growth could well turn negative by the end of the year,” said Oleg Kouzmin, an economist at Renaissance Capital.

"The most likely outcome for full-year gross domestic product is below 1%,” he said.

Meanwhile, the Economy Ministry refuses to accept this pessimistic outlook and is still officially forecasting 2.5% growth for the year.

Business spending aside, retail trade turnover — the total value of goods bought by households — grew by 2.1% in the first half of this year compared with the same period in 2024.

This is slower than the 10% growth seen in the second half of 2024 and the 7.7% growth for the whole of last year.

Putin leans on BRICs allies China and India

In light of the increasingly difficult economic choices confronting him to sustain the Ukraine war, Putin is heading to China to shore up a united front from his BRICS bloc allies.

Up until now, unprecedented levels of government expenditure on defence have been propped up by the ongoing sales of oil and gas to Russian allies like China and India.

However, oil export revenues have been on the wane due to sanctions and lower global demand.

Weighing heavily on Putin’s mind are the Trump Administration’s tariffs on India that are expected to discourage it from buying Russian oil.

As a result of these tariffs, Putin has displayed little to no interest in offers by Trump for a new round of bilateral trade talks.

Meanwhile, the fallout from the Trump Administration’s tariffs on India could severely impact Russia’s already stretched budget and force the Kremlin to consider other spending cuts or further tax rises.

Ironically, Ukraine’s decision to strike and paralyse 10 refineries throughout August has unwittingly freed up additional crude oil volumes for export.

By shutting down facilities representing 17% of national processing capacity (1.1 million barrels per day), Russia managed to increase its August crude oil exports by 200,000 barrels per day compared to the initial schedule.

However, if India reduces its oil purchases from Russia, it could further harm the Russian economy and potentially cause a rise in global gas prices.

Russia on dangerous path

While the Kremlin appears willing to tolerate a brief period of low growth, the bigger gamble is that the cooling of the economy won’t trigger a prolonged recession.

For the government to maintain defence – accounting for over 40% of expenditures - and social spending, Alexander Kolyandr, senior fellow at the Center for European Policy Analysis (CEPA), says it may need to cut elsewhere, which could potentially put it on a dangerous path.

Reduced spending or austerity measures could, adds Kolyandr, further slow economic growth and wage increases at a time when sanctions, low oil prices, and challenges to property rights discourage private capital investment.

“On the other hand, if the government doesn’t reduce fiscal support, there’s a risk high inflation will return,” Kolyandr said.

Meanwhile, inflationary pressures, prompted largely by the surge in defence spending, sanctions and labour shortages - that have caused imbalances in supply and demand in other industrial sectors – plus rampant food price hikes, are also on the Kremlin’s mind amid fears that the economy has been overheating.