As the trend cycle shortens and fast fashion is on the rise, luxury brands are scrambling to appeal to consumers.

This comes as earlier this year, LVMH reported disappointing first-half sales for the first half of 2025, with analysts suggesting this marks a broader slowdown for the rest of the luxury market.

The luxury market leader reported an 8% decline year-over-year in its Fashion and Leather Goods segment.

Fashion brand Burberry, earlier this year, also implemented strategies to mitigate a 17% fall in revenue by cutting 17,000 jobs worldwide by 2027, with Shein being the leading fast fashion brand.

On the flip side, fast fashion continues to rise, with the market being worth US$150.82 billion in 2025 and expected to rise to US$214.24 billion by 2029.

Micro-trends and storytelling

One of the key areas that fast fashion has capitalised on is microtrends, which consist of mini-trends that change on a frequent basis.

Due to their production model, fast fashion sites are able to mass-produce cheap products in a quick fashion.

“Social media has really made things, made cycles a lot shorter,” RMIT senior lecturer in business and economics, Marian Makkar tells Azzet.

“Micro trends are making people, particularly Gen Z, want to buy things faster rather than one or two quality items.”

However, over the past year, microtrends have been on the decline, leaving space for luxury brands to capitalise on what they do best: storytelling.

Despite this, University of Melbourne marketing and management lecturer Kanika Meshram tells Azzet many luxury brands have fallen for the trap of chasing profits and making their products a commodity rather than focusing on the culture and history that made them aspirational.

“A conversation for luxury brands to survive and be in this market is investing in that culture, pulling out narratives of sustainability and craftsmanship,” she says.

“These are avenues that they need to build on, rather than falling for trends or even thinking of fast fashion as a competitor down the line.”

Meshram says luxury brands turning their products into commodities has made it easier for fast fashion brands to create “dupes”, which are essentially cheaper, unbranded versions of more luxury items.

She also says that fast fashion brands were never primarily about fashion but instead about technology.

“It's a technology-driven model; design is never their priority,” Meshram says.

“They have not just excelled in a commodity, but they've excelled it on other values around the commodities and the speed at which they generate.”

Convenience

Makkar says accessibility of luxury brands can be a double-edged sword.

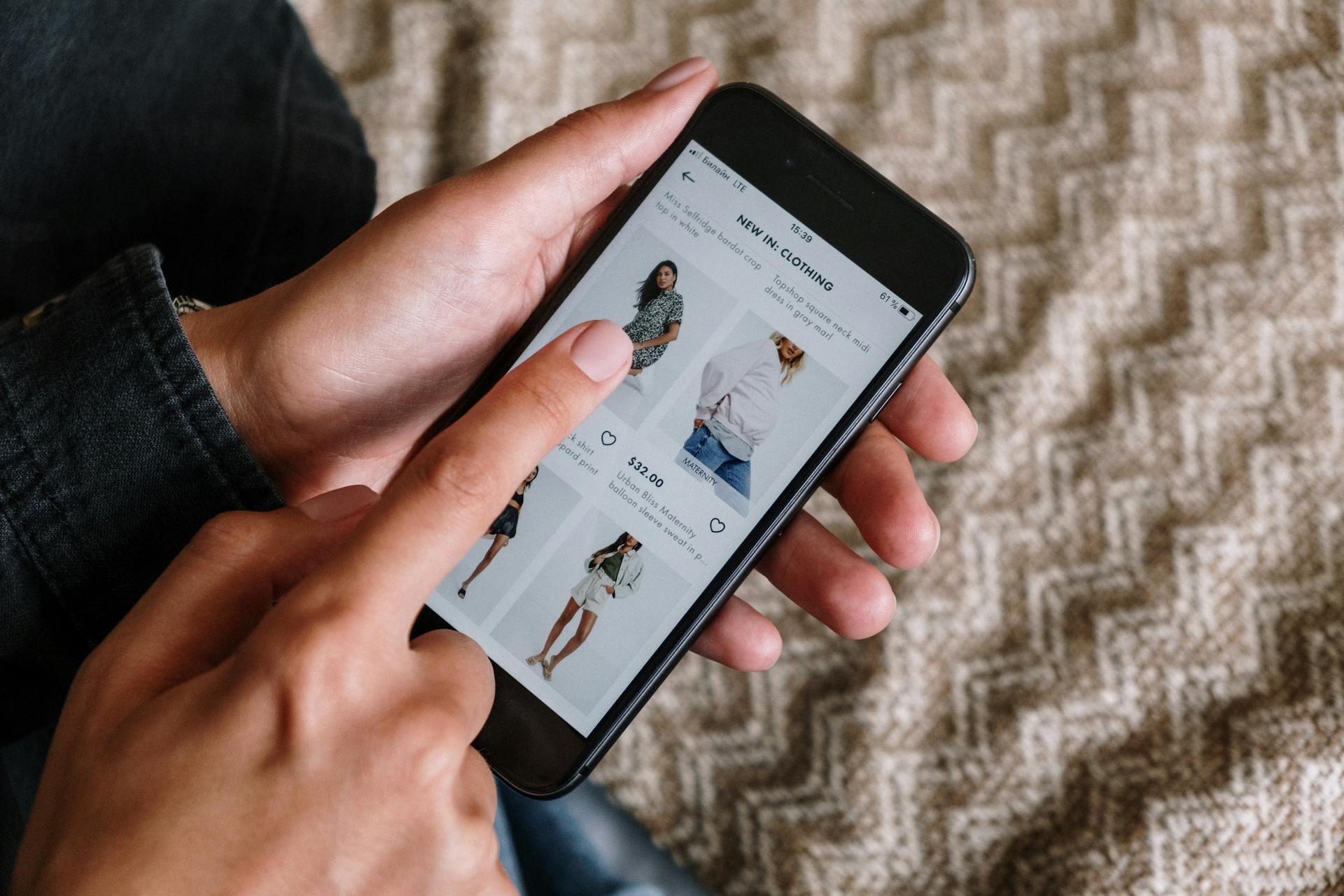

Lack of accessibility of luxury brands can give the upper hand to fast fashion brands, as they have become a more convenient alternative due to e-commerce, and 20.9% of worldwide fashion sales occur online.

“It's easier to buy something behind a screen and get the same look for half the price,” she says.

“It removes those barriers to purchase.”

While some luxury brands have created their own online stores, the majority of consumers would prefer to make their luxury purchases in person rather than online.

“Luxury brands are also available online, and they're doing this out of desperation, not because they want to be online,” Meshram says.

“They want people to come to their retail store and consume the whole culture about their production process, and somehow that is affecting their identity, where they stand against brands that are top of the mind.”

Despite this, 20% of all luxury purchases are online, with Gucci’s augmented reality shoe try-on feature driving a 300% surge in online sales.

Meshram suggests that luxury brands moving online is a quick fix to the threat fast fashion poses.

“I constantly call it the diet way or the Ozempic way,” she says.

“When you look at going on a diet, that's hard work, whereas Ozempic is a quick fix to everything.

“This is the narrative that's going on in the fast fashion world, where no one is really talking about the effort needed to rebuild and restructure the market.”

Environmental impact vs cost

The negative environmental impacts of fast fashion have consumers at a crossroads of whether to buy luxury items or the cheaper alternative.

In 2025, the fast fashion industry is responsible for 10% of the global annual carbon footprint, which is more than flights and maritime combined. It also uses 141 million cubic meters of water annually and contributed to 35% of microplastics polluting the ocean.

A recent survey showed that 58% of the consumer cohort born between 1997 and 2013 would seek to buy products that are sourced sustainably; however, 77% of Australians in that age range reported experiencing money concerns.

Meshram said Gen Z is in a transition period where they grew up with fast fashion as teenagers but are beginning to realise the environmental impacts.

“I think Gen Z's are the ones who are making the biggest shift to sustainable consumption and shifting away from fast fashion, which is a limitation of fast fashion brands,” she says.

However, this brings up a new issue of luxury resale, which has become a US$350 billion market.

“Sometimes they sell it to secondhand shops, and that ruins the brand’s exclusivity,” Makkar says.

Makkar says this issue could be mitigated by luxury brands controlling where they sell old fashions to and collaborating with artists for new designs.

“The way they can compete with fast fashion and resale brands is by just using that storytelling, that exclusivity, that craftsmanship and limited editions.”