While ticket prices rise and fewer people visit the cinema, one thing rings true: book-to-film adaptations do better at the box office.

A 2018 study found that film adaptations of books earn 53% more than original screenplays worldwide. RMIT associate professor in cinema studies, Stephen Gaunson, told Azzet that Australian book-to-film adaptations typically make 20% to 30% more at the box office.

Despite this, the Australian adaptation industry is still in its infancy, with attitudes towards them only changing locally in recent years.

Why adapt books?

Gaunson says studios opt for adaptations because they have a built-in audience.

“If audiences read the book and they think it looks pretty good, they're probably more likely to actually go out and see the film,” he says.

An example of an Australian-based film that Gaunson says benefited from the name of the book was The Dressmaker (2015).

He says marketing the film alongside the book gave it more success, with the film becoming the biggest grossing Australian film in 2015-16 with a box office gross of A$20,271,661.

“The Dressmaker was very much an event film,” Gaunson says.

“If you look at the advertising at the time, there were cinemas that were really promoting it as like the 'girls night out'.

“Rosie Ham, the author, was involved in the publicity for the film, so she was actually going to cinemas and sort of introducing the film.”

Even when book-to-film adaptations have questionable marketing strategies in relation to the book's content, they can still go far at the box office. Before legal battles between the film's stars arose, there was controversy surrounding the film's marketing as a girls' night out, considering the film's depiction of domestic violence. Despite this, the films worldwide tally still came to US$354,833,324.

The film was also made in the U.S., which Gaunson says, alongside the U.K., is one of the biggest markets for adaptations.

“If you actually look at America, I mean, the majority of what America has always done is adaptation in some form, like, whether it's sequels or franchises or, you know, book adaptations,” he says.

In the U.K., 52% of the top 20 films produced between 2007-2016 were based on published materials and earned US$91 million more per film globally.

These films also accounted for 61% of the total U.K. box office gross and 65% globally.

According to Gaunson, the adaptation films that tend to do best at the box office are franchises, like the Hunger Games and Harry Potter, or films targeted at a younger audience.

“Harry Potter was like a perfect example of it, where you've got queues of kids lining up to get the book, and then the same kids in queues lining up to see the film when it comes out,” he says.

“It's sort of this happy relationship with, with, with that demographic, because they're so they're so engaged in cultural works.”

Gaunson says these films can also act as a boost to the author due to the book getting more publicity and potential republishing deals.

“They can put, you know, stars from the movie onto the front cover, and they actually get a lot of sales by doing that,” he says.

“Even Stephen King, one of the best-selling authors ever, says that his career survives because of adaptations.”

Why is Australia lagging behind?

Despite adaptations reaching great heights on international markets, Australia has only just begun to take advantage of the formula.

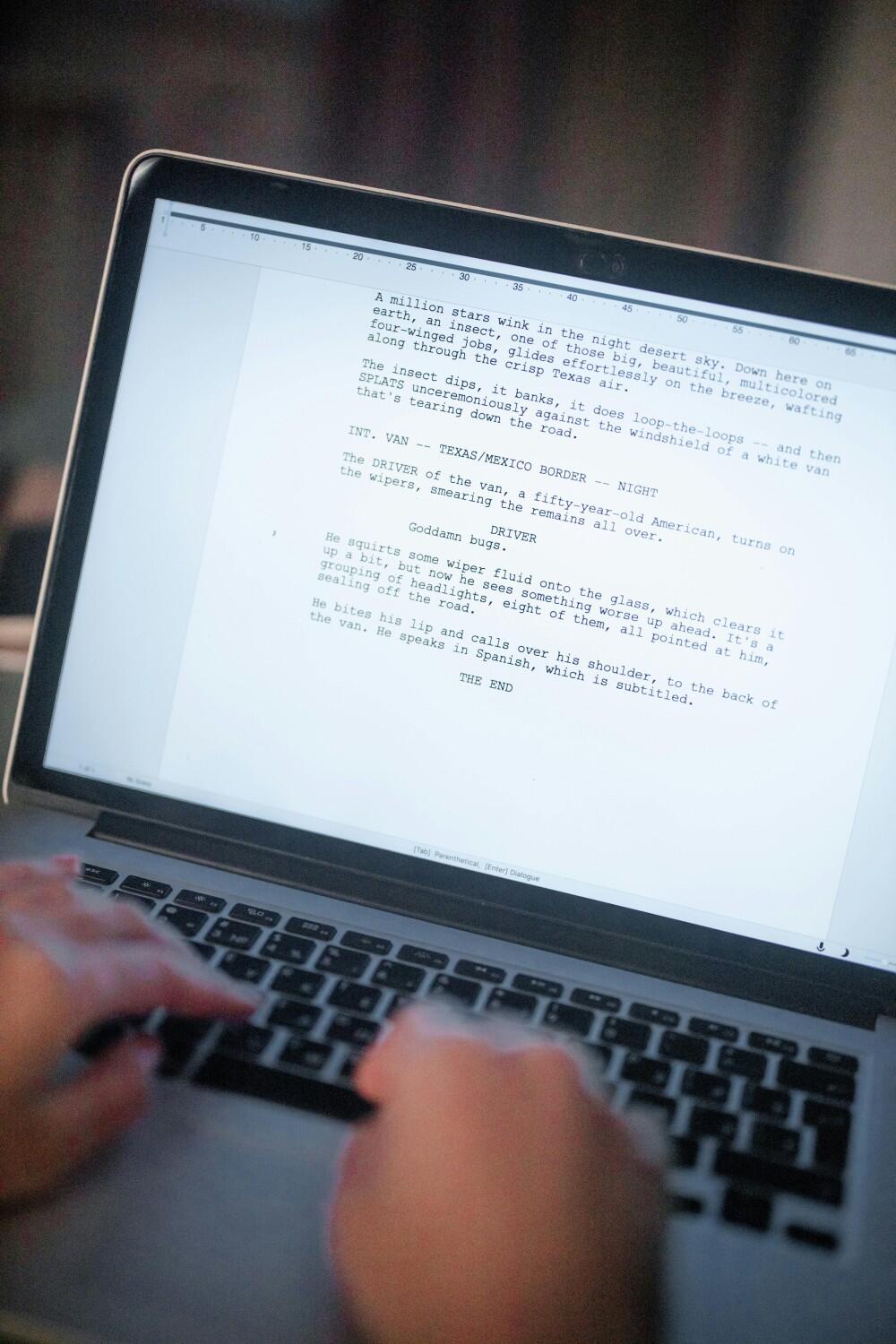

Gaunson says one of the key reasons for this was that Australian filmmakers were trained to create original screenplays.

This was due to the cost of adaptations.

“I think about 10-15 years ago, the idea was that an adaptation to option would cost astronomical amounts of money, and nobody in Australia had any money,” he says.

Gaunson says that while there were Australian adaptations in the past, many of them weren’t marketed as such.

“Films that did really well, like Picnic at Hanging Rock, Wake In Fright, Walkabout are actually adaptations, but no one was really talking about them as adaptations, because so many other films were coming out which were just original films,” he says.

However, there have been some recent adaptation films that have done well, including Paper Planes, which became one of the highest-grossing Australian films in 2015, earning A$9.61 million at the Australian box office.

Gaunson says this is likely due to the film having a younger audience.

“Schools got involved with that and they started to play Paper Planes for school students,” he says.

“Buses of school students would turn up at cinemas, and the kids would pile in to see the film.”

However, the tides are now changing with two book adaptations being part of the 15 projects to share in A$8.1 million of production funding courtesy of Screen Australia.