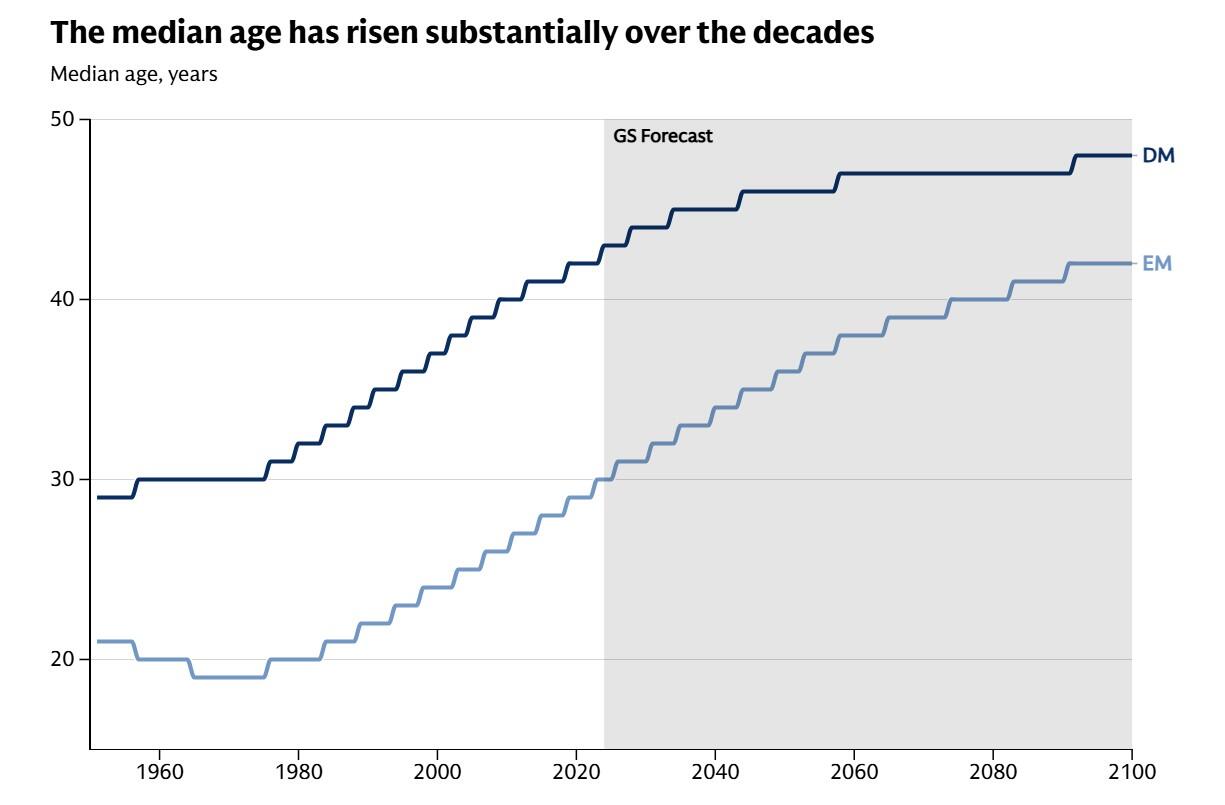

A ‘demographic time bomb’, - or so we are told - is ticking… as soaring life expectancies and falling fertility rates leave a shrinking workforce to support a burgeoning elderly population.

The prevailing narrative surrounding global demographics often paints a bleak picture and this scenario, according to conventional wisdom, suggests a protracted period of economic stagnation.

A recent report from Goldman Sachs Research posits a more optimistic outlook - suggesting that increasing longevity and healthier ageing could defuse this supposed bomb.

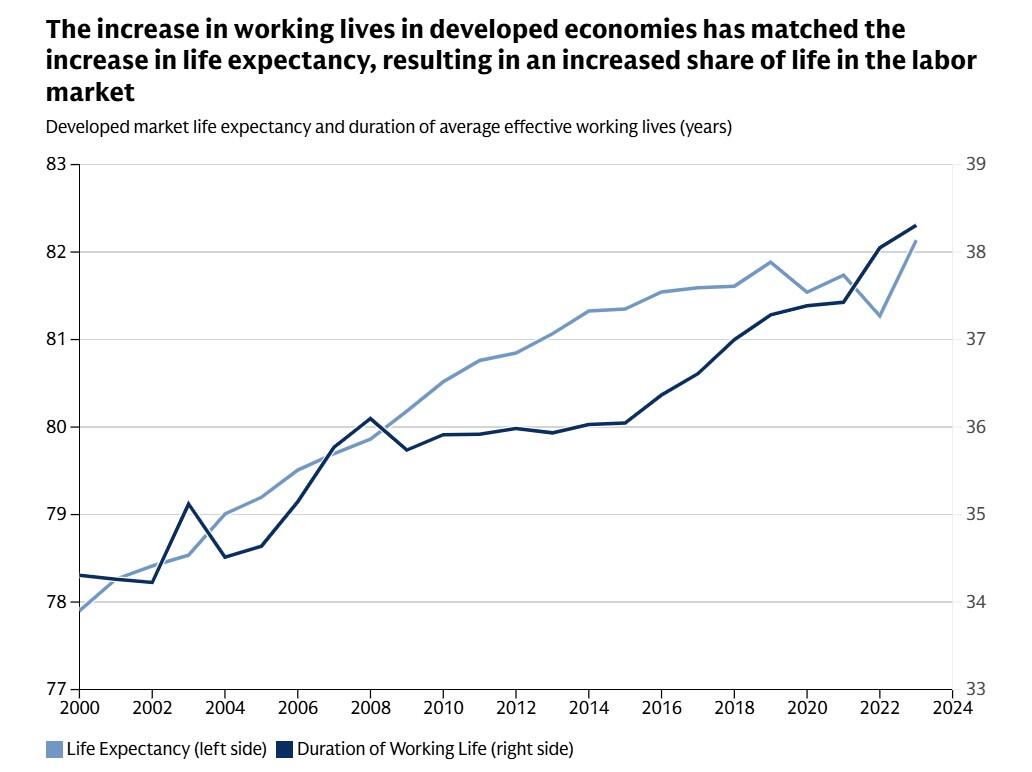

On the surface, the statistics can seem alarming. Goldman Sachs Research economics co-head Kevin Daly notes that in developed economies, the median life expectancy has climbed from 78 to 82 years of age since the turn of the millennium.

Over the same period, the proportion of the population considered to be of working age (15-64 years) has been in decline.

These trends would logically point to a drop in the labour force as a share of the total population - yet the reality has been quite the opposite. Daly revealed the share of the total population in employment has, in fact, increased.

The effective working life in developed economies has extended significantly, causing the dependency ratio - the number of dependents relative to workers - to fall, despite declining birth rates.

This shift towards longer working lives appears to be a widespread, adaptive response to living longer, rather than a direct result of policy changes.

The trend is notable even in countries with minimal alterations to their pension laws.

Daly says increasing life expectancy is fundamentally a good thing.

“Population aging is one less thing to worry about.”

Living longer, healthier and more unequally?

The extension of human lifespans is a near-universal phenomenon.

Over the past 50 years, the average global life expectancy has jumped from 62 to 75 years.

Crucially, however, we are not just living longer; we are living healthier for longer - however, this upward trajectory in longevity is coupled with a steep decline in global fertility rates.

Citing a recent International Monetary Fund study, the Daly highlights that a 70-year-old in 2022 possessed the same cognitive ability as a 53-year-old in 2000.

Daly says that people today are in better shape as they age than their predecessors.

“The fact that we are not only living longer but also slowing the process of aging throughout our lives raises an important economic point,” Daly wrote.

“In a very tangible sense, 70 is the new 53."

This optimistic view, however, is not without its caveats and the "health span" dividend may not be evenly distributed.

A recent evidence review from the UK's Centre for Ageing Better warns that older workers with long-term health conditions are disproportionately sidelined from work.

This suggests the reality of working longer is more accessible to educated, higher-income individuals than to those in physically demanding roles or with pre-existing health issues, reflecting an accumulated disadvantage over a lifetime.

New economic realities

A central anxiety surrounding an ageing population is the decline of the working-age ratio.

Goldman Sachs challenges the assumption that employment must fall in lockstep with this ratio, arguing that to assume this “appears unduly pessimistic.”

Encouragingly, this transition is already well established, with average working lives lengthening by 12% since 2000. Still, many analysts believe this adaptation alone won't be enough.

A June 2024 OECD analysis concluded that while extending working lives would mitigate the fall in GDP per capita, it would generally not be sufficient to fully offset it.

Even with greater workforce participation, the rising costs of healthcare and pensions for a larger cohort of retirees will test the sustainability of public finances, a point consistently raised by institutions like the European Central Bank.

And then there's concerns about productivity that persist. While research from Boston College's Center for Retirement Research finds little evidence that older workers reduce firm productivity, it notes they often cost more - potentially squeezing profitability.

This is balanced by the economic potential of the ‘longevity economy’.

A 2024 report from the Brookings Institution highlights that the 50-plus population is a powerful consumer force, projected to drive significant spending growth and create new markets for goods and services tailored to their needs.

This creates a more complex picture as the adaptation to an ageing population appears to be happening organically, as Goldman Sachs suggests.

But as others indicate, this does not eliminate significant hurdles related to fiscal strain and inequality.

Data suggests that as we live longer and healthier lives, the definition of a working life is evolving alongside it - presenting not a simple crisis or a seamless transition - but a fundamental, and often complex recalibration.