The automotive dealership experience has devolved from a polite financial transaction into a stress test of consumer patience - at least in this Azzet writer's experience - with prices spiralling upwards and inventory becoming strangely specific when pushed out onto the showroom floor.

Sales reps look visibly exhausted trying to move models that skirt cross-border tariff rules through awkward supply chains, and market indicators have been flashing red for months without anyone truly understanding the growing structural fracture.

The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development's (OECD) How important is the automotive industry in OECD countries? Insights from supply and use tables, published last month, provides a technical schematic for this dysfunction.

While the market reacts to the immediate fallout of tariff policies enacted in April and frantic C-suite reshuffles, the OECD has laid out the blueprints of a building that is currently burning down.

Utilising Supply and Use Tables (SUTs), the organisation has produced an x-ray of the global automotive skeleton, and the diagnosis suggests the industry’s bone structure is buckling under the weight of geopolitical fragmentation.

Let's look under the hood…

Bratislava > Berlin

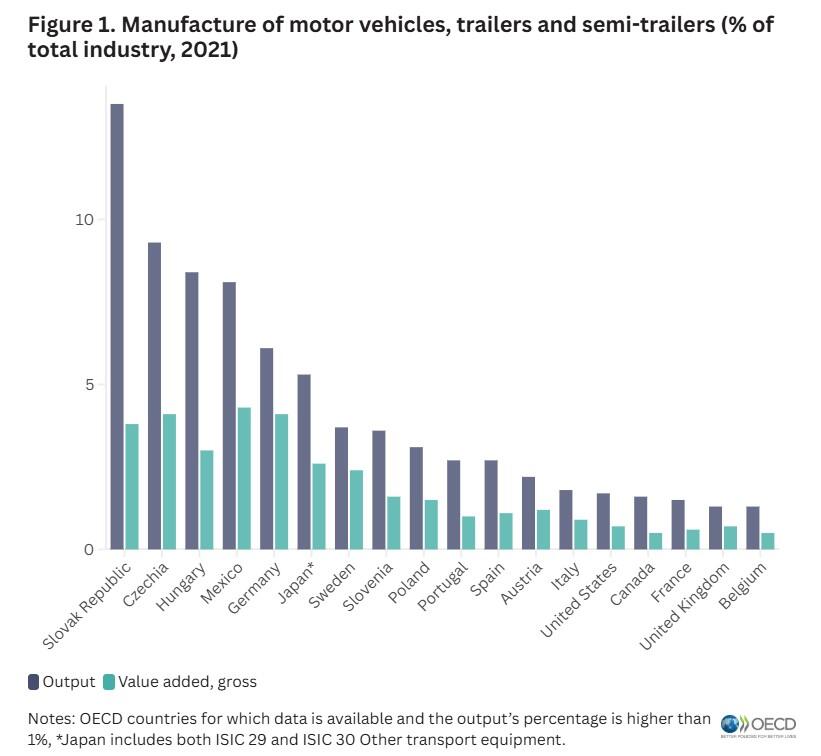

While the Americans, Germans, and Japanese dominate auto industry headlines in absolute terms, the OECD report identifies a different set of nations when analysing true economic dependency.

The beating heart of the OECD’s automotive reliance metrics is actually located in places like Bratislava or Prague, with the Slovak Republic reigning as the heavyweight champion of macroeconomic exposure for its manufacturing.

Slovakia's auto sector accounts for a staggering 13.5% of its total output, followed closely by Czechia at 9.3% and Hungary nipping at its heels.

For these economies, the trade volatility of late 2025 is a structural threat rather than a quarterly dip, largely due to a metric the OECD calls “intermediate consumption”.

In countries like the Slovakia and Belgium, the auto industry consumes a massive amount of its own products, indicating a production chain that is fragmented, specialised, and hyper-efficient.

These nations do not build cars from scratch so much as they assemble components manufactured elsewhere in a cross-border relay race.

When major economies introduce 25% tariffs on imports, this hyper-efficiency immediately transforms into a massive liability.

Tariff stacking

The global market in general has spent the last two quarters dealing with "tariff stacking," and the OECD’s detailed breakdown of import dependency explains the supply chain mechanics of the damage it's been doing.

Because the industry is deeply integrated - importing intermediate goods to create exports - a single tariff applies multiple times as a part crosses borders.

By the time a transmission moves from a forge in Mexico to an assembly plant in the US, it has accrued cumulative duties that completely distort the final pricing structure.

Market reaction has been swift, with companies like Subaru forced to reinvent their logistics maps overnight by shipping vehicles directly from Japan to Canada to bypass the US tariff wall.

Production halts in Chicago earlier this year are a direct result of this fragility, representing evasive manoeuvres mandated by the mathematics of supply chains rather than standard maret adjustments.

The OECD report contrasts this with countries like the UK and Italy, where the production process is more integrated and domestic.

Legacy manufacturing hubs, previously criticised for lacking efficiency, are now accidentally insulated from border costs because if you manufacture the steel, the bolts, and the chassis in the same postcode, you don't have to worry about border taxes.

EV slowdown, margin squeeze

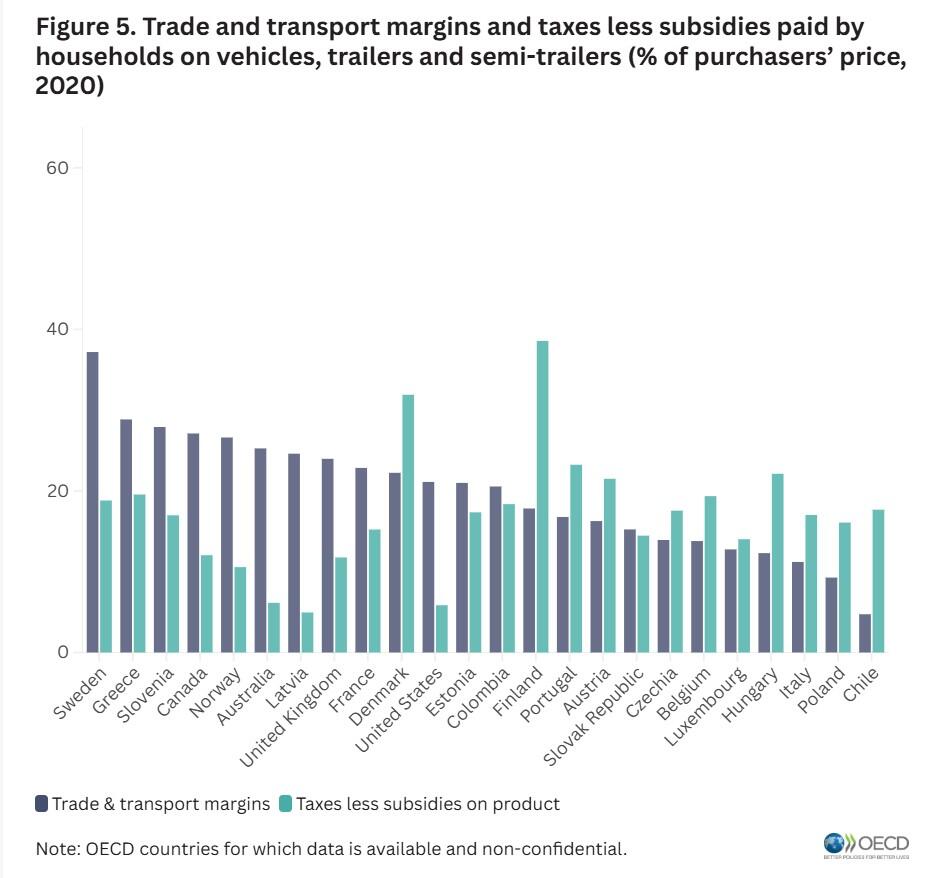

The OECD report illuminates "trade and transport margins" - the markup between the factory gate and the consumer - which in several OECD nations account for nearly 40% of the final vehicle price.

This margin compression collides with slowing EV growth in the West, where forecasts peg expansion at a sluggish 1.6% globally for the year.

When a 25% tariff is applied to a battery pack and a 30% dealer/tax margin is added, the consumer value proposition basically evaporates.

The OECD explicitly notes that high margins in countries like Sweden - over 35% - are often driven by the portfolio of car brands and lack of domestic plants.

Meanwhile, taxes in Finland hit 39% while Latvia sits at a comfortable 5%, proving that the impact of trade and transport margins is as responsible for the pricing crisis as the cost of battery technology.

The servicification of manufacturing

Analysts also touch on a less visible but equally critical trend: the servicification of the automotive sector, where value is derived from R&D and software rather than physical assembly.

This shifts the "smile curve" of value creation, pushing profits to the ends of the chain (design and sales) and hollowing out the middle (manufacturing).

For countries like Germany and Japan, this poses a complex challenge because their industrial models are built on high-value manufacturing, which is now being tested as software becomes the dominant cost centre.

In France and Germany, the service content in automotive exports is rising, but this also increases reliance on cross-border data flows and intellectual property protections.

Trade barriers in 2025 are not just about physical goods; they are beginning to encroach on the digital services that keep modern cars running.

Case in point: Stellantis

Stellantis, a 2021 amalgamation of car brands such as Dodge, Peugeot, Fiat, RAM and Chrysler, provide a clear case study for the fragmentation risks identified in the OECD report.

With a portfolio that integrates European engineering with North American assembly, the conglomerate faces significant logistical hurdles under the current tariff regime.

Their reliance on the flow of components between Europe and North America has exposed the company to "tariff stacking," resulting in increased operational costs and inventory accumulations.

The decision to temporarily suspend production at facilities in Italy and the U.S. Midwest reflects the difficulty of moving parts across borders while maintaining profit margins.

Meanwhile, BMW and Mercedes-Benz rely on a business model where value is driven by engineering complexity and brand prestige, necessitating a manufacturing base concentrated in Central Europe.

East beats West

China's automotive industry structure, on the other hand, presents a completely different picture entirely - nearly half of all new cars sold there being electric, their domestic "use table" operates on different fundamentals.

In contrast to Western legacy challenges, Chinese manufacturers are executing strategies to reduce what the OECD terms “import dependency”.

BYD for instance utilises a high degree of vertical integration - manufacturing batteries and semiconductors in-house - which mitigates the impact of component-level tariffs.

It's actively bypassing trade barriers by establishing regional production hubs in Hungary and Mexico - effectively moving their supply chain inside the tariff walls of key markets.

Automotive giant Geely is adopting a similar approach through its brands Volvo and Polestar, shifting the production of key models like the EX30 and EX90 to Belgium and South Carolina.

They are building a self-sustaining ecosystem less vulnerable to Western policy shocks.

While the West disputes component taxation, the East is vertically integrating the entire production cycle.