Another nail in globalisation’s coffin may just have been hammered as Europe faces up to a reality where it needs to re-industrialise on the coat-tails of the United States' globally significant trade changes.

The European Union is starting to feel the economic effects of an escalating U.S.-China trade war as new data shows direct and indirect ~20% tariffs could shave off 0.3% of eurozone GDP growth over the next two years.

EU industrialisation in general has lagged behind the U.S. these past two years. At the start of this year, industrial production in the EU was ~5% lower than the 24 months prior, yet levels across the Atlantic have remained stable.

Meanwhile, China recorded a 13% rise in production growth during that same timeframe.

Making matters worse, the ongoing war in Ukraine and a subsequent energy crisis is also leaving its mark with three to five times higher energy prices than American or Chinese competitors squeezing profit margins.

The continent is already feeling the pinch from a blanket 10% tariff the Trump administration laid on all goods going into the U.S. and while there are concessions rumoured to be made, a 25% tariff remains in place on steel, aluminium, cars and auto parts too.

Also looming are additional tariffs in play on pharmaceuticals and semiconductors which will likely cause more worry.

US demand for EU goods slow

ING Senior Sector Economist Edse Dantuma says that as long as tariffs remain in place and uncertainty about further and higher levies lingers, the U.S. will probably no longer be a growth market for European goods.

“Eurozone exports to America has increased materially before tariff announcements were made, and the most immediate effect will be the reversal of imminent frontloading which will bring extra downward pressure on industrial production in the second quarter,” Dantuma wrote in an ING trade report.

The U.S. is the largest export market for European products, with a share of 20% of extra-EU trade. It also makes up 22% of Germany and Italy - and a whopping 46% of Ireland.

France and the Netherlands are less exposed, with 16% trade ties, while Spain's exports to North America come in at 13%.

“Pharma is most exposed to US tariffs, but machines, vehicles, and chemicals [are] also greatly affected,” Dantuma said.

“While the pharmaceutical sector was among the best-performing European industries in 2024, the outlook for this year is much less rosy. Trump specifically mentioned pharmaceuticals (along with semiconductors) as products excluded from general tariffs, but they'll soon be subject to specific tariffs.”

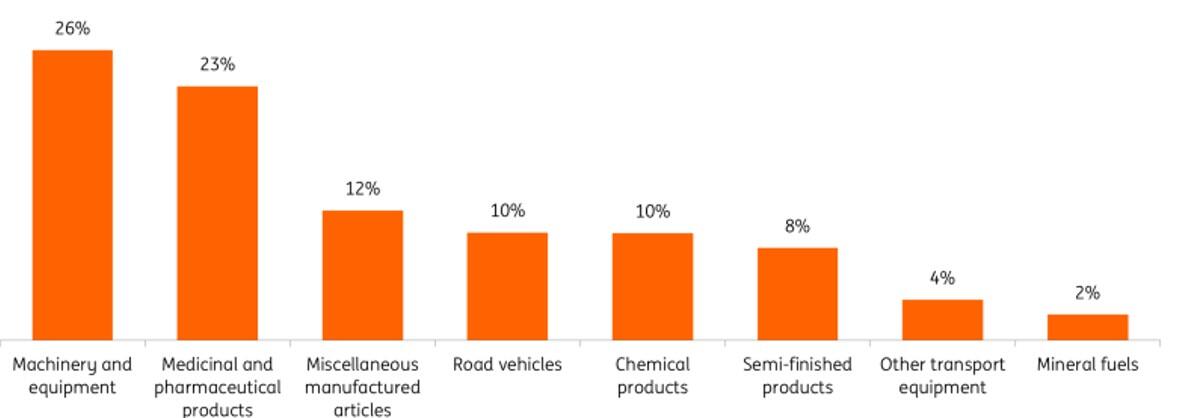

Should this materialise, pharmaceuticals and medicinal products that made up 23% of > €530bn in goods the EU exported to the U.S. last year will be hit hard.

For Europe's pharmaceutical industry itself, 38% of its exports head to the U.S., compared with an average of 20% for other major industrials such as machinery, vehicles and chemicals.

Germany's auto industry is driven to the brink

The tariff impacts are dealing other exposed manufacturers in Europe such as the automotive industry - which was already desperate to reverse stagnating trends - a huge blow.

Especially in Germany, where its carmakers account for a fifth of its manufacturing GDP through global household brands such as Volkswagen, BMW, and Mercedes-Benz.

Between 2017 and 2023, cars sales by VW fell from 10.7m to 9.2m, BMW from 2.46m to 2.25m and Mercedes-Benz down from 2.3m to 2.04m vehicles.

Last year saw all three carmakers' profits fall by >30% - lower than already low expectations.

“Germany has effectively been an export-driven market, and once those markets sneeze, Germany catches a cold.”

And downward pressure is being felt across the associated steelmaking industry too.

“From the Thysenkrupp and Salzgitter steel mills producing sheet metal rolls that are later turned into doors and bonnets, to makers of smaller components used in drivetrains,” Schmidt Automotive Research's Matthias Schmidt told the BBC.

Yet while some of the pressures facing Germany's auto industry were not foreseeable, there was still an element of complacency, says Schmidt.

“They knew the structural issues were there, but were blindsided by cheap Russian gas [for years].

“Germany has effectively been an export-driven market, and once those markets sneeze, Germany catches a cold, which is what's happened.”

So how can Europe reinvigorate its struggling industrial sector? There are a few positive movements afoot.

Military industrial complex to lead green shoots of a turnaround

Apart from potentially lower policy rates for businesses, Edse said two key factors could offset some of the impact of the trade war on the economy and manufacturing.

“Firstly, long-awaited additional German investments that aim for stronger defence and infrastructure improvements – including transport, (clean) energy and digitisation – could support EU manufacturing demand from 2026 onwards,” Edse wrote.

“Secondly, the European Commission’s plan to ‘rearm’ Europe and to unlock extra defence spending is set to boost industrial growth.”

Growing Europe's military capabilities would generate about €800 billion, says the Commission.

According to the plan, boosting growth of the European Union's military and industrial complex could potentially unlock €650bn if countries allocated an extra 1.5% of GDP to defence, raising average EU defence spending to 3.5% of GDP.

In addition to a planned €150 billion in joint European defence loans, the European Commission is considering shifting an existing €392 billion in the 'cohesion fund' for regional development to strengthen member states' defence capabilities.