Making sense of a company’s drill results is never as easy as it should be. That’s because a mining company’s new discovery or drilling update is typically written by geologists who struggle to put mining-speak into everyday language that you the would-be investor can understand.

At the other end of the scale there’s the ‘pump and dump” brigade that junior mining stocks sometimes hire to spruik every ounce of blue sky out of the results.

So between the sublime and the ridiculous, you need guidelines to know what a good drilling result looks like when you see it.

Where to start

While making sense of drill results, resources and reserves may appear to be more art than science, there are some useful benchmarks to help guide you through.

Without getting lost in the minutiae of detail, here are a few initial terms that you’re going to regularly come across, so you need a layman’s understanding of what they mean.

Measured, indicated or inferred

For starters, it’s important to understand that not all mining results are born equal.

Sometimes a mining company may want to have a bet each-way on its early results by referring to them as either ‘measured’, 'indicated', or 'inferred' based on what the latest round of results are telling them.

A ‘measured’ resource – due to its physical characteristics like shape and density – gives geologists greater degrees of confidence than an ‘indicated’ resource in being converted to a proven ore reserve or a probable ore reserve that’s more economically significant.

While an ‘indicated’ resource may only be converted to a probable or reserve, inferred resources with the lowest confidence cannot be converted to a reserve.

Other useful terms

Before delving into what a good grade looks like, here are a few other useful terms that geologists who prepare an ASX announcement for the market regularly use.

Ore Reserve: This is simply the resource that an explorer plans to mine and will typically be determined by a feasibility study (discussed in Part 2) and can be proven (higher confidence) or probable (lower confidence).

Proved Ore Reserves: These are typically deemed lower risk and lower cost relative to indicated and inferred/probable ore reserves.

That's because the two latter typically require more expensive and extensive drilling and analysis to progress them into measured resources/proved ore reserves.

Location: Where an explorer’s resource is located can tell you a lot about future potential threats and opportunities.

For example, while proximity to other known mines and/or infrastructure includes road, rail, ports, water, and power can help to derisk a project, while projects in war-torn countries pose sovereign risk issues.

Contiguous: This typically refers to single, large resource offers where the economies are typically better than several smaller deposits spread over a wider project area.

Depth: The shallower resources can be found the easier, and cheaper they are to extract.

Open: Being ‘open at strike’ typically means drilling is yet to discover the boundary of the deposit along the predicted directions the deposit is expected to run.

By comparison, being ‘open at depth’ means drilling is yet to find the deepest boundary of the deposit.

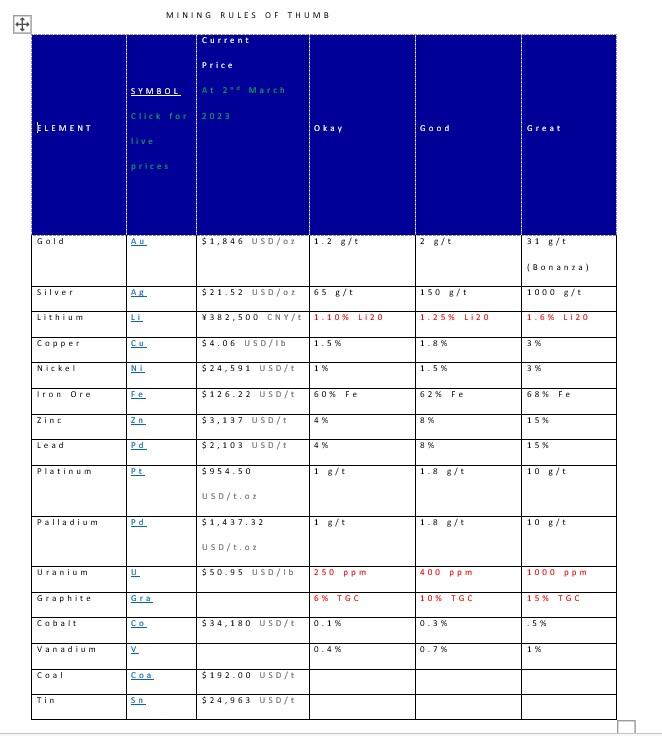

Know a good drill result when you see it

When miners talk about grade they’re referring to the concentration of the mineral they’re looking for in the ground.

It’s important to remember that the grade will depend on the mineral an explorer is looking for.

While a geologist could bore you tearless explaining a comprehensive study of the grade, here are some guiding principles on which your future knowledge will grow.

Copper: Greater than 1.0% is commonly used as the threshold for high-grade copper deposits.

Gold: Shallow deposits, as low as 1-2 grams per tonne or ore (g/t) are considered a good grade. However, in deeper deposits, miners want to see at least 4-5 g/t.

Lithium: 1.5-2% millimolles per litre (mmo/L) is typically regarded as a good grade.

Uranium: Resources are typically quoted in U3O8 - aka Yellowcake - which is roughly 85% elemental uranium.

A grade of 0.10% of U3O8 (i.e., 1000 parts per million) is indicative of currently mined uranium deposits.

Anything over 1% uranium is typically regarded as high grade.

Intercepts: Generally, the bigger and shallower the intercept, and the higher the grade, the more valuable the drill result.

Simply put, intercepts relate to the length at which the mineral grade was indicated in the drill core sample.

Within a gold explorer’s drill report you might see "20 metres at 2.5g/t Au from 100 metres" what does it mean?

This simply indicates that gold was found in the stated concentration (i.e., grams per tonne) in a 20 metre span from a depth of 100 metres underground.