A first-of-its-kind dataset has uncovered US$57 billion (A$91.77 billion) of targeted financing by China into the developing world’s resources sector over a 22-year period and expanded its control of critical minerals supply chains across the globe.

Full-stack tracking of China’s official sector financial commitments for copper, cobalt, nickel, lithium and REE extraction and processing operations across 165 low-income countries and middle-income countries over a 22-year period has been collated and analysed.

The comprehensive Power Playbook: Beijing’s Bid to Secure Overseas Transition Minerals report by AidData shows that an extensive network of 26 official sector creditors from China have collectively bankrolled these transition mineral projects.

Notably Beijing’s policy banks - the Export-Import Bank of China (China Eximbank) and China Development Bank (CDB) - have played a major role during the period, extending nearly US$32 billion of credit between them.

For more than two decades China, the new rich kid in town, has been using similar brands of “economic diplomacy” with poorer nations in the same way the West did with it in the past - using first Shanghai and then Hong Kong as British-owned autonomous trading hubs - of which the latter was finally handed back to the Chinese in 1998.

So how did it come about?

From Panda Diplomacy

The term “Panda Diplomacy” originated from the practice of gifting pandas and dates back to China’s Tang Dynasty (618–907 CE), when Empress Wu Zetian reportedly sent a pair to Japan.

Those early exchanges were ancient gestures of peace and goodwill. Yet in the modern era, the term has evolved to symbolise a sophisticated blend of conservation, soft power and international economic strategy.

It all kicked off as China emerged from the developing world in the 1990s through cheap labour and cost-cutting which positioned it as the go-to country to import manufactured goods from, driving its GDP exponentially to become the world's second-largest economy.

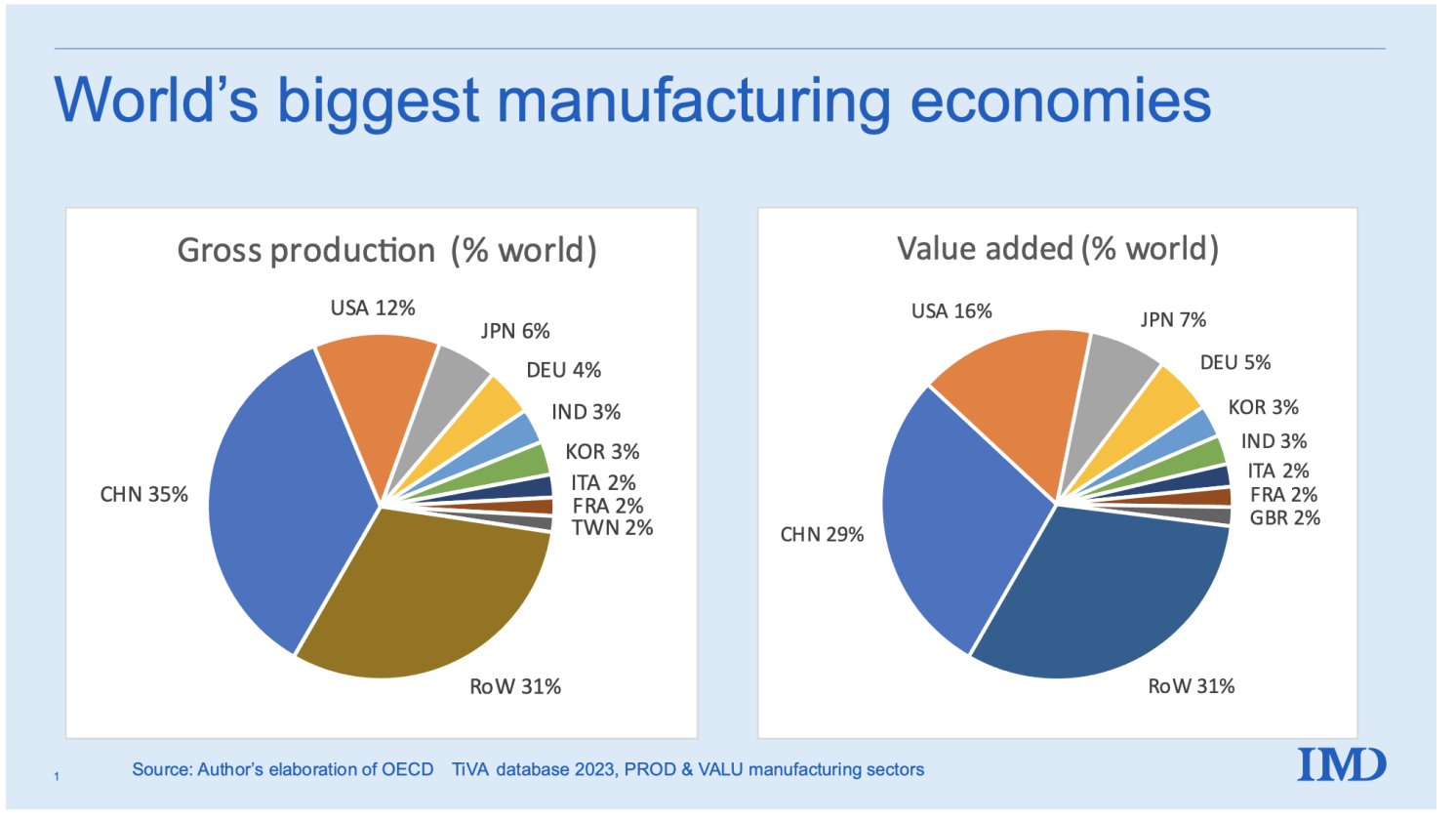

Nowadays it commands more than 35% of the world's manufactured goods and has since embarked on major infrastructure projects outside its borders such as its multi-billion-dollar Belt and Road Initiative (BRI).

Its aim? To build land and sea economic corridors from its western border across to Europe - a modern version of the ancient Silk Road.

To debt diplomacy

A widely cited case of how China's tactics to saddle developing nations with unsustainable debt was its deal to build Sri Lanka's Hambantota port on the nation's southern coast as part of its BRI initiatives.

Between 2007 and 2012, Sri Lanka's Rajapaksa government secured loans worth over US$1 billion from China’s Exim Bank to finance the construction of the port, despite widespread doubts about the project’s profitability.

Sri Lanka initially approached other potential creditors, including India and the Asian Development Bank (ADB), but failed to secure financing due to profitability concerns.

Ultimately, the Rajapaksa government turned to China, which offered loans at significantly higher interest rates - around 6.3% - compared to the 3% the ADB would have charged.

Once the port was completed, it failed to generate sufficient revenue and as Sri Lanka's economy was tanking it repaid the loan for the port's construction by handing the Middle Kingdom a 99-year lease over the port.

China now hosts military vessels at Hambantota, providing it with regional power projection across the northern Indian Ocean.

Debt financing

Using syndicated lending instruments, Beijing is taking a de-risking shortcut by outsourcing risk management to third-party lending institutions.

In the year 2000, there was not a single link to these types of loan deals for mining and energy projects stemming from the Chinese government, yet by 2021 syndicated lending equated to nearly 80% of its transition minerals loan portfolio.

Now, a whopping 74% of the Middle Kingdom’s official lending portfolio to poorer nations is made up of loans to institutions and entities that have secured repayment guarantees from host government institutions - qualifying the money lending as publicly guaranteed (PPG) debt.

Beijing “rarely uses PPG loans to bankroll transition mineral operations in the Global South and has prioritised limited recourse project finance transactions rather than full recourse sovereign debt transactions”, the report says.

Roughly 81% of China’s transition mineral lending portfolio in developing countries currently qualifies as non-PPG debt.

About the same percentage of the portfolio supports project companies - including special purpose vehicles (SPVs) with a single shareholder and joint ventures (JVs) with multiple shareholders - without host government repayment guarantees.

OK, so what does this all mean then?

China's US$57 billion investment has now created high-demand mineral supply chains that streamline from 10s of thousands of kilometres away straight into its domestic industries.

The limited recourse project finance model offers Beijing something that the full recourse sovereign debt model cannot: opportunities to control the overseas production and sale of critical minerals that it has a shortfall of at home.

In mining sector JVs and SPVs, the primary output is raw or processed mineral ore which are typically allocated among the shareholders of JVs/SPVs based on their equity stakes.

These mineral ore allocations are formalised through so-called “offtake agreements” that specify how much of the mine’s output each shareholder receives. Shareholders can then sell or direct their shares of the output as they wish.