When Warren Buffet’s first wife Susie died with an estate of about US$3 billion (A44.6 billion), just $10 million went to their children and the rest was distributed to the family’s foundation.

“These bequests reflected our belief that hugely wealthy parents should leave their children enough so they can do anything, but not enough that they can do nothing,” the world’s most famous investor said.

The so-called Oracle of Omaha first made this statement in 2006 and repeated it last month when announcing he would give away almost all of his US$150 billion (A$231 billion) fortune to charities overseen by his three middle-aged children.

Buffett’s line has been line regularly quoted in discussions about the transfer of wealth and goes to the heart of a decision facing many wealthy people in Australia as they consider what to do with their vast fortunes.

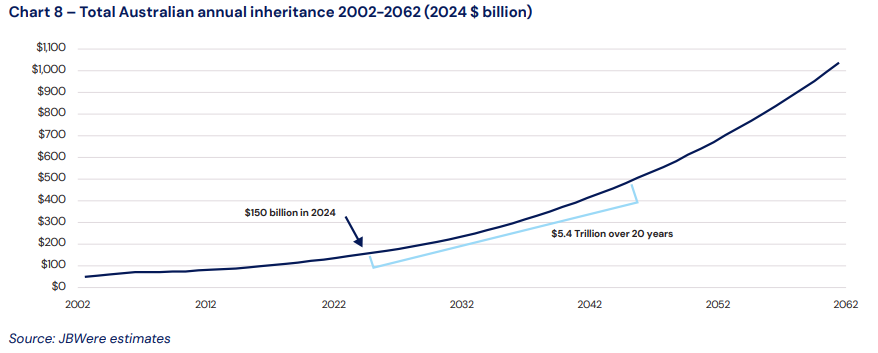

The Productivity Commission estimated in its Wealth Transfers and Economic Effects research paper issued in 2021 that $3.5 trillion would be transferred to the next generation of Australians over the next two decades as Baby Boomers retired.

This forecast was raised to $5.4 trillion by investment manager JB Were in The Bequest Report.

Around the world, the numbers are much larger with wealth manager UBS estimating about US$83.5 trillion ($128.5 trillion) of wealth will be transferred in the next 20–25 years, according to its Global Wealth Report 2024 report.

“We have created mind-blowing wealth in this country (Australia) in recent decades. Most of it is new. But we haven’t created a strong giving culture,” said philanthropy adviser and consultant Peter Winneke, the author of Give While You Live.

Winneke attributed the reluctance to make and publicly disclose large donations to the “tall poppy syndrome” in Australia and the ego associated with “keeping up with the Joneses”.

“We don’t stop to think about how much we need to maintain our lifestyles. We could transform the size of the philanthropic sector overnight if we stopped leaving everything to the kids,” he said.

He noted there were high profile exceptions to this such as iron ore magnate Andrew ‘Twiggy’ Forrest and his wife Nicola who have created the $8 billion Minderoo Foundation, one of Australia’s largest philanthropic organisations.

Australia has only about 2,000 private ancillary funds, the tax-effective philanthropic trusts that allow people to make tax-deductible donations to charities, but Winneke believed there should be 10,000 to 15,000 now.

Australia lags the USA and UK for giving

Justin Gilmour, the founder of Perth-based wealth management firm Integro Private Wealth, said Australia was a considerable way behind the United States in terms of philanthropy with only half of Australians earning $1 million a year giving to a charity.

“It's very different in America which is a lot more sophisticated in terms of where they’re at with their program of philanthropy,” Gilmour said.

He said Perth, the capital of the resources rich state of Western Australia, had the highest concentration of wealth in Australia, but only 10-15% of his clients wanted to pass on some of their wealth to charity.

“It’s changing in Australia but it’s driven around tax concessions a lot of the time. It’s an education piece in that they don’t know how to start. In the private wealth space we do see a trend where they’re actively looking for opportunities,” he said.

Considerations for those planning philanthropy including establishing the right structure, such as using a private ancillary fund, the size of the giving program and how much the next generation needed to reach their potential.

“If you put the money into a private ancillary fund, once the money is in there, it can’t go back. When you don’t use the right structure and the funds are just left without guiding principles, that’s when it can go pear-shaped,” he said.

About 10 years ago donating to charities would not have come up in conversations but clients were now more involved, with people aged 25 to 35 driving their family’s philanthropy programs.

“Families are choosing charities where their kids and grandkids can be (involved),” Gilmour said.

Investment manager JB Were said only 1% of Australian inheritances were left to charity, well below the levels in the United States and United Kingdom, once assets were passed to partners, the next generation, other family members and friends.

The firm said although Australia ranked highly in the world on wealth and the proportion of people writing a will, it was well below average on the proportion of people who made a charitable bequest and on the proportion of inheritances given to charity.

JB Were recommended that the challenges and disincentives associated with leaving super to charity be removed as this would help to address the fact that the number and size of bequests falls once people retire although they have fewer expenses.

For many Australians most of their net wealth outside of their home is held in superannuation where the national asset pool has reached $4 trillion, much of which is managed by the largest funds such as UniSuper.

The $136 billion fund said charities could not be validly nominated as dependents for super but some fund members split their beneficiary nominations between their children and their estate so money could go to a charity under their wills.

“When positioned well, clients are receptive to the idea of ‘giving with warm hands’ — that is, making gifts or leaving a legacy before they pass away. We do know clients make bequests in their Wills to various charities, but this is usually arranged directly with their solicitor,” a UniSuper spokesperson said.

Wealth management firm Koda Capital said one of the most persistent issues identified by its clients was how they should share their wealth with their family in the most effective way possible, without causing problems for their children or themselves.

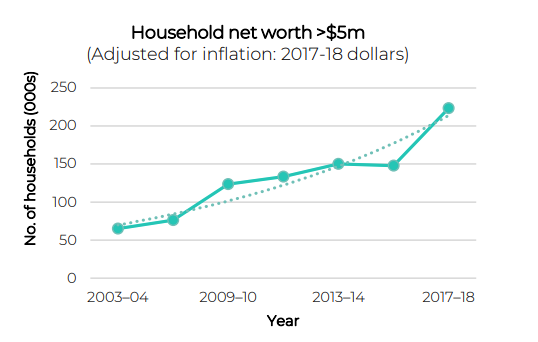

The issue was compounded by increasing wealth and smaller families with more money being divided among fewer people.

“Despite increased prevalence, there remains no guaranteed path to the successful deployment of capital, family harmony or a one-size-fits-all answer to the question of “what is the right thing to do?” Koda Capital Partner James Hawthorne wrote in the Helping your kids without ruining your life (or theirs) paper.

Philanthropy set to boom in Australia

Peter Winneke expected donations to charity to increase significantly given that the minimum wealth required for inclusion in the Australian Financial Review Rich List was about $700 million and about 15,000 Australians earned more than $1 million per year.

“I am really optimistic about philanthropy. I think it will explode due to the weight of money. It just needs role models giving away material sums and talking about it,” Winneke said.

“If you pick the right organisation you will create positive change in the community. You are leaving the world in a better place than you found it. Family foundations can be an incredible education tool for the next generation.”