Virgin Australia 2.0 could be the next airline to land an IPO on the ASX’s tarmac of broken dreams

With around 300 airlines of varying sizes coming and going in Australia's aviation history, there’s one thing we know for sure: It takes more than deep pockets to keep an airline flying, but also profitable.

Since mid-2024, Australian travellers have witnessed the collapse of low-cost carrier Bonza and more recently the closure of Rex, the long-time regional airline of small turboprop aircraft born out of Ansett’s ashes.

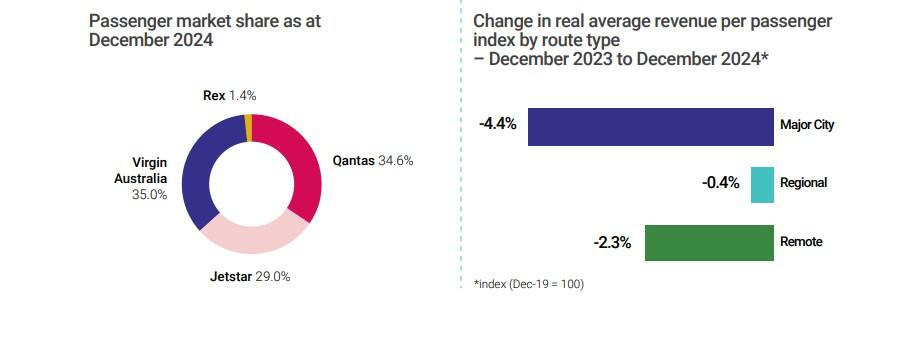

What we’re left with is a duopoly comprising Qantas (ASX: QAN) – euphemistically called the national carrier - and its unlisted counterpart, Virgin Australia (Virgin). As at December 2024 ACCC data reveals that Australia’s passenger market share was divided between Rex 1.4%, Qantas and its budget-airline subsidiary, Jetstar 65%, while Virgin controls slightly under a third (29%).

Virgin’s well-heeled backer

Late February, the Foreign Investment Review Board (FIRB) approved the sale of 25% of U.S. private equity Bain Capital’s (Bain) 95% stake in Virgin to Qatar Airways, with Virgin founder Richard Branson continuing to own the airline’s remaining 5%.

Since the Gulf carrier took a 25% stake in Virgin, the competition regulator has approved a wet lease agreement between the two airlines.

Virgin's plans to use Qatar's planes, crew and service mean the airline will return to long-haul flying in June this year, with initial flights from Sydney, Brisbane and Perth to Doha. Once Melbourne is added to the itinerary in December, the Virgin/Qatar deal will see 28 weekly return services between Qatar's capital Doha and the four Australian capital cities.

Virgin is now awaiting a decision from the International Air Services Commission (IASC) on an uncontested allocation of air rights for services between Australia and Qatar, due to commence in June.

Meanwhile, what was clearly attractive to Qatar was Virgin’s current status as a domestic carrier only.

Virgin’s re-relaunch 2.0

Qatar’s 25% control of Virgin has also galvanised Bain's plans to take the company public. Bain clearly thinks that having a wholly-owned subsidiary of the Qatari government, Qatar Airways on Virgin’s share register will be a big plus for money markets. This is when you float.

With his feet now under the CEO’s desk, recently appointed CEO, Dave Emerson – who replaced the previous Virgin CEO and fellow American Jayne Hrdlicka and former Bain consultant - has been tasked with convincing local fund managers to support the airline’s re-listing on the ASX. Formerly the airline’s chief commercial officer, Emerson will hope Virgin’s ASX relaunch 2.0 makes a better fist of being a public company than former CEO Paul Scurrah. He was ousted following the airline’s near collapse.

Virgin entered into administration in April 2020 under the strain of the Covid pandemic – owing $6.8 billion to creditors including employees, bondholders and customers.

Virgin subsequently delisted from the stock exchange which is when it fell under Bain's control which bought the ailing airline for $3.5 billion including liabilities in 2020.

Since then the airline has struggled to successfully position itself as a hybrid airline that sits between a full service operator like Qantas and its budget counterpart, Jetstar.

Lessons from the Qantas playbook

Listed airlines that operate within the highly cyclical aviation sector emerged strongly from the Covid downturn. This helps to explain why Qantas recently delivered one of its near-best financial results ever.

Armed with Qatar Airways on its share register, coupled with near optimal market conditions, Emerson is expected to move quickly with float plans.

Since its collapse in 2020, Virgin has returned to profitability in FY23 for the first time in 11 years. In FY24 the airline boosted its earnings by 18.2% to $519 million.

However, at 10% Virgin’s margins remain well behind Qantas domestic at 16.1% and Jetstar at 15.2% – which is something a listed entity will clearly plan to address. Everything being equal Virgin’s ASX re-listing will be one of the biggest floats of 2025.

Emerson will take his cue from Qantas which emerged from some dark days back in 2023 when it fielded accusations of anti-competitive behaviour, sky-high airfares, and nepotism, into what’s now seen as a post-pandemic success story.

A clean set of books

At the half-year mark, Qantas' statutory profits climbed 6% to $923 million. The company reported underlying profit before tax (underlying PBT) of $1.385 billion for the first half 2024/2025, a $140 million increase compared to the first half 2023/2024.

The group’s statutory profit before tax (PBT) was $1.320 billion, an increase of $75 million compared to the first half of 2023/2024, and statutory profit after tax was $923 million. Investors should note that statutory profit includes the increase in legal provisions concerning the ground handling outsourcing Federal Court case. This was not included in the underlying PBT.

Statutory earnings per share were 59.9 cents per share, group operating margin was 12 per cent, operating cash flow was $2.07 billion, and net capital expenditure was $1.43 billion.

Fleet of foot

However, one of the issues confronting Qantas is the age of its fleet – one of the oldest in the world – and the constant maintenance of older plans is contributing to heightened flight delays and cancellations.

Virgin already boasts fewer flight delays and cancellations than its larger rival. Much of this can be attributed to its investment in updated, more fuel efficient aircraft during FY24. During the year it deployed six new Boeing 737 MAX-8 aircraft and 14 Boeing 737-800 aircraft.

While Qantas has also added new planes, the biggest upgrades are yet to come. Given that the airline already has around $4 billion in long-term debt on its balance sheet, a complete fleet upgrade could be a protracted affair.

The speed at which it can bring more modern fleet offerings to market could be a source of future competitive advantage for Virgin.

A more modern fleet offering would advance Virgin’s plans to capture an increased market share of long-haul flights.

Virgin’s IPO and float

Given that market conditions don’t get better than they are now, Emerson knows that when staging an IPO, synchronising with market appetite is critical: In capital markets this is called ‘feeding the ducks while they’re quacking,’ and leaving it too long can be disastrous if market appetite starts turning.

Mike Murphy, a Sydney-based partner at Bain told the market earlier this year that the firm plans to retain a significant shareholding in a future Virgin Australia IPO.

Bain has not disclosed its net round of IPO plans, but earlier this year the private equity firm sent a request for proposals for the listing to investment banks.

Investors and banks want to know how much stake Bain plans to retain after an IPO. Assuming Bain takes its cue from other private equity-led IPOs in Australia, which typically sell at least 50% of their stakes to ensure liquidity, Bain will be left with a stake of around 20% or potentially less.

Private equity behaving badly

The market has a long history of private equity firms, like Oaktree Capital and Apollo Global Management buying distressed assets, including Nine Entertainment for a song. They strip out costs, and then staging profits when they finally refloat.

However, in recent years regulators have tried to limit how long private equity firms can retain shares in a stock brought to market during a float and/or IPO. Investors can also take comfort from the recent successful listing of Guzman y Gomez (ASX: GYG) which was brought to market by the stock’s largest shareholder, private equity fund TDM Growth Partners (TDM).

While TDM Group has been involved in several other high-profile IPOs including Baby Bunting (ASX: BBN), Tyro Payments (ASX: TYR), and Pacific Smiles Group (ASX: PSQ), so too has Bain.

As the fifth largest private equity firm in the U.S. Bain has invested in more than 600 companies globally and taken over 50 of them to IPO.

Optimal conditions are waning

Since President Donald Trump's ascent to the White House, market conditions for anything, let alone IPOs have soured. Add the cyclical nature of airlines to current economic headwinds and money managers may struggle to find Virgin’s upcoming float appealing.

While Qantas’ last result dodged most of the consumer fallout from Trump’s presidency, U.S. airlines weren’t so lucky. Last week alone, four U.S. airlines trimmed their outlooks, citing weak consumer demand amid broader market uncertainty around Trump’s trade tariffs and other reforms.

One of the biggest cost imposts affecting all airlines, jet fuel, projected to rise to $115 per barrel in 2025.

According to ATPI’s Airline Industry Outlook, the global airline industry is set for a positive 2025, with capacity and passenger demand expected to exceed pre-pandemic levels. However, the report also flags key challenges such as supply chain disruptions, geopolitical uncertainties, with rising operational costs continuing to shape the industry’s trajectory.

The report also singled out both Qantas and Virgin for experiencing supply and maintenance challenges, further delaying full recovery.

What’s next

Assuming market conditions don’t deteriorate too much, Bain and its bankers and lawyers (Barrenjoey, Goldman Sachs, UBS, Reunion Capital and Gilbert + Tobin) are expected to dust off the initial prospectus they prepared over a year ago.

Assuming they do, Bain is expected to pull the trigger on its listing and IPO during the June quarter.

If they don’t, the doors for any future float may close fast, at least for now.

Qantas has a market cap of $13.8 billion making it the 40th largest stock on the ASX; the share price is up 72% in one year and up around 2% year to date.