AirTrunk, the largest data centre operator in the Asia Pacific region, attracted a lot of attention for its A$24 billion buyout in September, but what may have been lost in the blaze of publicity was the significance of a debt refinancing transaction year earlier.

In August 2023, the burgeoning Australian-based company doubled the size of its corporate sustainability linked loan (SLL) to $4.6 billion to refinance debt and support rapid expansion across the region.

This deal shone a spotlight on the fast-growing private credit market in Australia, which the professional services firm EY (formerly Ernst & Young) has estimated to be worth $188 billion at the end of 2023.

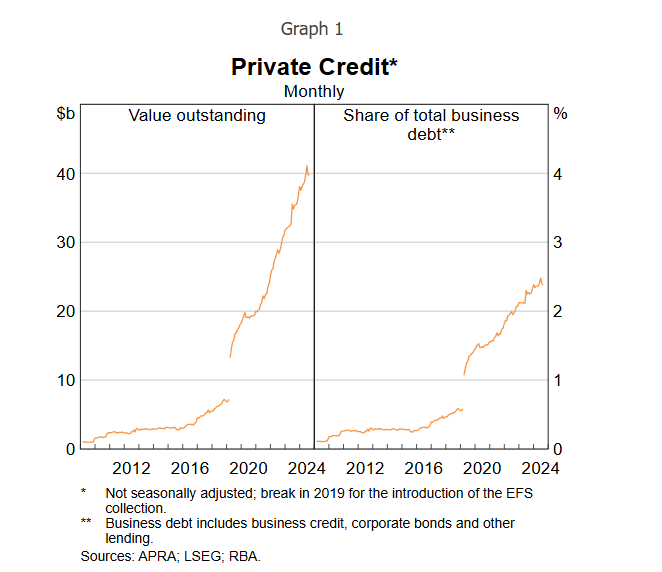

The Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) put the value of the Australian market at $40 billion but this estimate does not include non-syndicated direct lending by superannuation funds.

The central bank also noted that, although the private debt market in this country was relatively small (2.5% of total business debt), it was growing rapidly.

In its Annual Australia private debt market update for 2024 published in February, EY said the AirTrunk loan was one of the private debt lending opportunities that was well supported in 2023, particularly as competition increased and pricing tightened.

Almost a year after the debt transaction, a consortium led by U.S. private equity giant Blackstone bought AirTrunk from Macquarie Asset Management and the Public Sector Pension Investment Board for an enterprise value of more than $24 billion.

Rapidly growing market

EY Senior Manager Transactions and Corporate Finance Oceania Fiona Hong said the Australia private credit market had grown at an annual compound rate 23% between 2015 and 2023.

The lenders are non-banks that typically intermediate between the investors providing the funds, such as superannuation (pension) funds, insurers, family offices, sovereign wealth funds and high net worth people, and the borrowers that need them.

Hong said the drivers of this growth included increasingly attractive risk adjusted returns as the cash rate increased, with return hurdles ranging from 7% to 15% bringing in money might have otherwise sat in cash or other asset classes.

Large American, British and European institutional providers of credit lending were expected to come to Australia as they saturated their home markets and diversified into this time zone into a country with a familiar legal landscape and no language barriers.

“As the sector begins to mature, we are forecasting [market] growth of 13% p.a. (over the next 5 years). This rate is far higher than the estimated growth in the bank and bond markets (we think mid-single digit growth),” Hong told Azzet.

EY said in its market update in February that activity in 2024 was expected to pick-up in after a slower period of mergers and acquisitions, project finance and real estate development-related financing in 2023.

“With a more stable interest rate and inflationary outlook, improved credit margins and existing private debt portfolios performing well, private debt lenders are poised to play a leading role as activity re-emerges this year,” the firm said.

“They also remain ready to support the capital needs arising from the economywide energy transition and related regulatory changes taking place.”

In 2023 as the year progressed competition increased and pricing tightened in the bank lending market, particularly for higher quality middle-market or investment-grade corporate deals.

As banks increasingly restricted lending to top tier borrowers like those that were number one or two in their sectors, well capitalised and trading well, private credit was stepping up to fund other borrowers.

“Some like to provide capital to ‘bank adjacent’ businesses, while others are funding smaller organisations (including loss-making start-ups),” Hong said.

“Consequently, they play an important role in the financial system and the economy. You want cost effective debt to be available to as many borrowers as possible.

“Cheaper than equity, the capital supports innovation, competition and underpins a vibrant economy.”

The risks of private credit included capability and know-how becoming stretched as the number of players approached 200, illiquidity and loan failures.

Banks withdraw as others step in

University of Sydney Professor of Practice (Global Economy) Hugh Harley said private credit loans typically carried a higher interest rate than other loans, had a higher risk profile than mortgages and required a higher capital allocation, reducing returns.

“That makes this sort of loan more difficult to assess unless there’s an existing relationship (between the lender and borrower),” Harley said.

He said the higher capital allocation and difficulty of assessing the credit risk explained the fact that some of the Australian banks had stepped back.

“But institutions and private individuals that are not subject to the same regulations might have expertise in that part of the market and a greater risk appetite,” Harley said.

“In that part of the market it’s not unusual for people to be charged 15% sometimes but (some lenders) feel that’s not such a bad opportunity, particularly those with a diversified portfolio.”

He noted private credit was not new, with banks, solicitor’s trusts and private organisation providing such loans in the less credit-constrained environment of the mid-1980s.

But improved bank credit practices following the banking crisis of the early 1990s, increasing capital requirements after the global financial crisis (GFC) in 2007 and the fact that mortgage lending had been so profitable meant banks stepped back.

Harley said although increased attention on the high returns offered by private credit may attract investors who did not understand the risks, he did not expect to see “mums and dads jumping” into the market.

The Australian Investment Council (AIC), which describes itself as the “voice of private capital in Australia”, said traditional bank lending to small and medium-sized businesses had contracted since the GFC, opening up opportunities for private lending.

The AIC said the “major banks” dominated the Australian credit space before the GFC but measures implemented by the Australian Prudential Regulation Authority (APRA) had changed the playing field for private credit.

This was exacerbated in recent years by market conditions which had been more favourable to equity investment over corporate bonds.

About 15% of loans to SME and middle-market businesses are estimated to be provided by non-banks.

“This shift to non-bank lenders is expected to continue in the short to medium-term,” the AIC said in its Private Capital document.

“While private credit transactions are predominantly through senior loans, Australia is experiencing a growth in the secondary market which provides another avenue of investment opportunity to build diversification, manage portfolio allocations and enhance returns.”

Related content